By Camilo McConnell, RAY Conservation Fellow,

Two of the Puget Sound region’s most well-known natural forces are rain and salmon. Rain sustains much of the natural beauty of the area while salmon serve as a point of cultural pride and identity, sustaining livelihoods for generations. Rapid urbanization, though, has upset the relationship between salmon and rain.

A recent study led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Blake Feist, “Roads to Ruin: Conservation Threats to a Sentinel Species Across an Urban Gradient,” demonstrates that during precipitation events, stormwater runoff produced “is unusually lethal to adult coho that return to spawn each year in urban watersheds.” In natural ecosystems, rainwater infiltrates the soil and recharges underground water tables — an integral part of the water cycle.

But urbanizing cities have replaced natural landscapes with roads, bridges, buildings, houses, highways, parking lots and other forms of impervious development. Every time it rains, rainwater lands on impervious areas, picking pollutants that accumulate on the surface. This produces a toxic runoff that goes into storm drains and roadside ditches. Often, this toxic runoff goes through our storm drains untreated, traveling directly into creeks, rivers and Puget Sound. Because of this, stormwater runoff remains the No. 1 source of pollution to Puget Sound, affecting human and fish health in the basin.

For salmon that travel in the creeks and rivers that flow into Puget Sound, the toxic mix can be deadly. According to the report, “40 percent of the total area of the Puget Sound river basins that support coho are predicted to have adult mortality rates that substantively increase the risk of local population extinction.”Coho salmon are especially susceptible to the deadly effects of stormwater, becoming disoriented, gaping, losing equilibrium and dying within a few hours of entering stormwater-affected streams.

To understand the long-term ecological impact of stormwater on coho populations, the NOAA research team has spent more than a decade documenting coho mortality rates in urban streams. They pay particular attention to pre-spawn mortality rates in females, which arrive in the fall to lay their eggs in stream gravels. Depending on the creek, however, 60 percent to 90 percent of the fall run of females die with their bellies still full of eggs due to the toxicity of the water. Because each fish only spawns once in its life, there is no second chance to start the next generation.

Big Project, Big Impact

A project in Fremont demonstrates the possibilities when developers are motivated to go above and beyond to address stormwater management.

Generally, runoff contaminants can include “sediment, nutrients (from lawn fertilizers), bacteria (from animal and human waste), pesticides (from lawn and garden chemicals), metals (from rooftops and roadways) and petroleum byproducts (from leaking vehicles, combustion engines, and tire wear).”However, adult coho salmon mortality does not seem to correlate with these conventionally measured water-chemistry characteristics. And since “hundreds or even thousands of distinct chemical contaminants in urban stormwater runoff have never been toxicologically characterized," the exact cause of death remains unidentified.

So, the search continues to identify the specific pollutants in stormwater runoff causing coho salmon death. Recently, researchers at the University of Washington's Center for Urban Waters, NOAA, Washington State University's Stormwater Center and the UW’s department of Civil and Environmental Engineering are pioneering new methodologies to identify organic pollutants in stormwater and fish. What they are finding matches the NOAA study “Roads to Ruin” — motor-vehicle-derived contaminants are the likeliest cause of coho mortality, with acetanilide, a stabilizer for rubber in tires, the most newly identified toxicant showing up in both stormwater, fish gills and liver.

While definitive research about the cause may not yet exist, what is known is that salmon remain the most iconic and culturally and economically significant species in the Pacific Northwest. “[Salmon] are central to the identity and traditional practices of indigenous peoples, vital for recreational and commercial fisheries, and keystone species for inland ecosystems as sources of marine-derived nutrients.” Coho salmon are a sentinel species — their health illustrates how polluted stormwater affects human and marine life — and will continue to into the future.

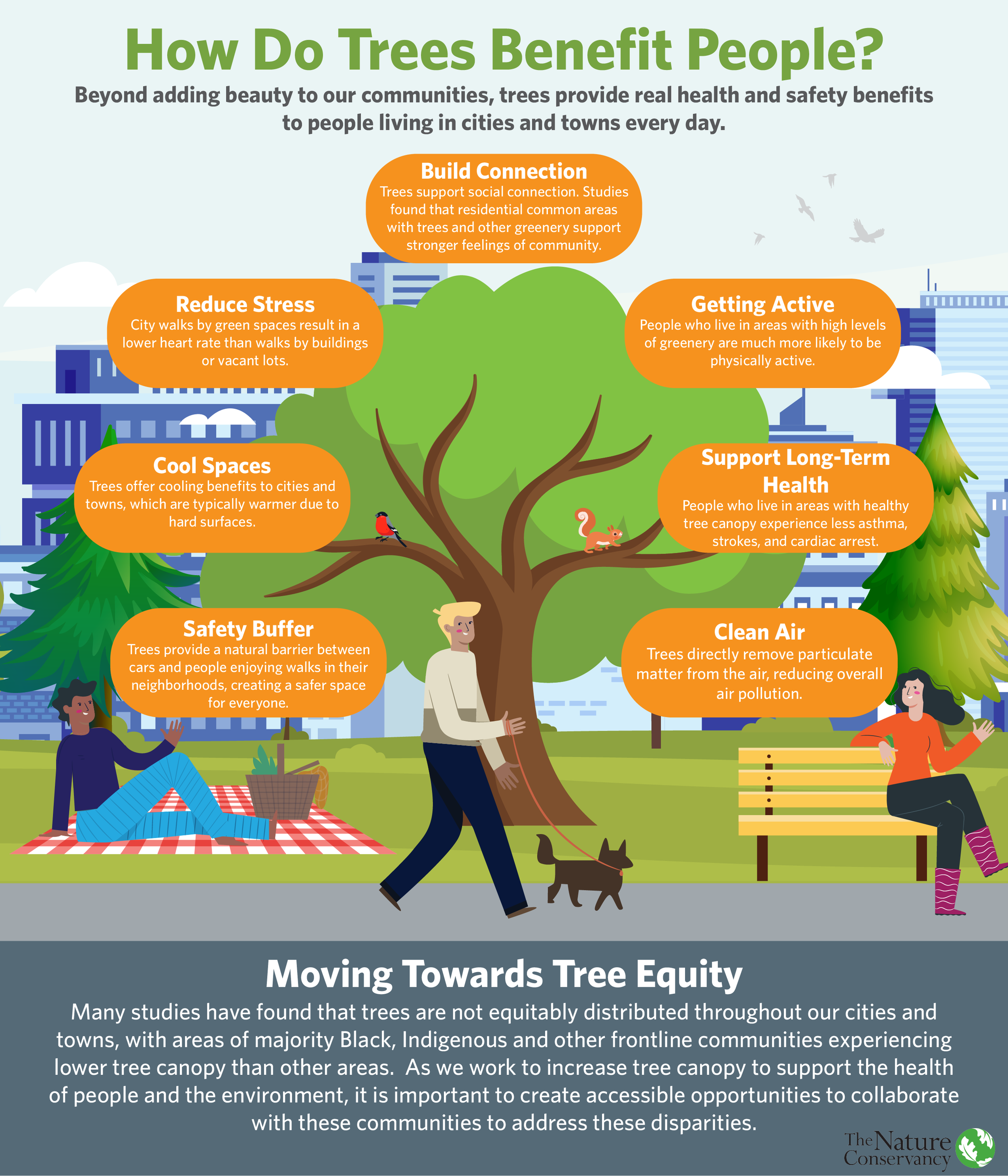

We need to work together to begin solving the challenge of stormwater pollution to support the health of freshwater and marine ecosystems, including salmon and people. Part of the solution is better integrating cities and nature. The study highlighted in the report looked at how green-stormwater infrastructure can address polluted stormwater. The team at NOAA conducted an experiment where coho salmon were placed into tanks with polluted stormwater runoff — 100 percent of them died. When the salmon were placed into tanks with polluted stormwater that had been filtered by soil media — all the salmon survived.

By incorporating green-stormwater infrastructure into our cities, we are bringing back the ecological functions that once dotted the landscape. Nature has always provided the best solutions, it’s now up to us to reintegrate those solutions to our cities.