The Northeast Washington TREX brings participants into a collaborative environment designed to increase shared stewardship and learning across agencies.

Controlled Burn Planned for Roslyn Forest Health and Safety

A Critical Ingredient to Washington's Hops

Written by Kara Karboski, Kristen Taggart & Ryan Anderson, Washington RC&D Council

Photographed by Heather Hadsel

Washington State is a land shaped by fire and water. Mighty rivers have formed our landscapes and help to support wildlife, power our homes and cities, and water our farms. Likewise, fire has existed in the forests, prairies, and shrub-steppe of our state for thousands of years as an important agent of change and rejuvenation.

Toward the Yakima Valley, the Naches and Yakima Rivers flow out of the Cascade Mountain’s forested slopes in central Washington State and into the Columbia River. The Yakima River is one of the most productive watersheds of the Columbia. Unique folds in Columbia basin basalt (LAVA!) combined with gravel and sediment created vast floodplains that once were, and soon will be again, critical habitat for upwards of a million adult salmon returning to the Yakima Valley throughout each year.

CelebrateForests and Beer with OktoberForest

The water that runs from the snow and forests of the Cascades has become a vital economic driver in modern times. The valley’s sun, soil, and irrigation supply, along with its hard working community, have created a hop industry that supplies approximately 70% of the nation’s hops. That means 70% of our beer is dependent on reliable, clean water that originates in the forests of the eastern Cascades.

September and early October bring familiar and odorous reminders that Yakima is “Hop Town, USA.” Crews cut hop vines off of trellises and haul them to various processing facilities while the familiar smell of beer’s most distinct flavoring agent – hops – drifts through town. Occasional whiffs of smoke from prescribed fires blow through town as well. These autumnal smells are both important to the beer industry and to the forest. Beer needs clean water that has been filtered and stored in healthy forests. The dry forests of the eastern Cascades need occasional low-severity fires to protect them from devastating fires and to preserve their necessary function of providing clean water.

But our forests are unhealthy. Natural fires, started by lightning during the dry months, used to dance their way across the eastern forests of Washington. These low- to moderate-severity fires are necessary for the health of the forests and served to burn through the vegetation on the forest floor returning nutrients to the soil, naturally thinning the forests, opening up the understory for new plant growth, and creating important habitat for wildlife. Periodic fires like these reduced the available build up of fuels for the next fire, continuing the cycle of low- to moderate-severity fires.

We have been very effective at fighting fires to protect forest resources and communities. This has resulted in the suppression of natural fire which would otherwise reduce the buildup of dead vegetation. With higher fuel loads, fires burn hotter and faster. And these fires are much more difficult and costly to fight. These megafires are consuming resources – economic, environmental and human – at an unacceptable rate.

Megafires can affect water supplies in devastating ways. Without vegetation to slow down the movement of water, it can move large volumes of soil, ash, and other sediment. Although sediment movement, landslides, and debris flows are all normal processes in the Cascade Mountains, they can occur at super-natural scales if our forests suffer burns that are also super-natural. During Washington’s Carlton Complex Fire, for example, massive debris flows destroyed infrastructure such as irrigation systems, roadways, and buildings. When debris flows like this occur above reservoirs or water intake structures, capacity of those systems can be lost for long periods of time or indefinitely. This is on top of the water quality lost due to more silt running into waterways. These events change the clarity of water, its taste and odor, and can result in other adverse effects on water.

If our forests are not treated, through mechanical thinning or planned and coordinated burns called prescribed fire, a highly destructive fire could cause a disruption of our clean, reliable water, impacting our hop production, drinking water, and brewing industries and create major expenses for water users.

Healthy forests and the reliable water they produce are not just for beer, but for the benefit of all downstream communities. Some communities are recognizing the risk from uncharacteristically large and destructive fires and the potential impacts these fires would have on their clean water supply. In New Mexico, a community in the Santa Fe Watershed recognizes the value of healthy forests for providing clean water. This type of investment is also seen in the Rio Grande Water Fund. Communities are recognizing the risks and are protecting their watersheds with investments from utilities and other funders that depend on healthy forests.

In our state, the Washington State Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network is working to connect communities that live in fire prone areas so that they can learn from one another, share resources, and support each other when fires affect them. Understanding the impacts of fires on our water resources is one piece of this complex issue, and communities are coming up with local solutions that work best for them.

The Yakima Valley is blessed with hops and beer, forests and fish. Both fire and water play an important role in supporting these natural resources. We can protect these resources and our communities by recognizing the role fire plays, both good and bad, and by addressing these risks for the benefit of all.

Read about our work in Yakima Valley

Learn more at OKtoberForest.org

Bringing Fire Back onto the Quinault Indian Nation

Story and photos by Adam Martin, Prairie Restoration Specialist, Center for Natural Lands Management

With the roar of the Pacific Ocean in earshot, Moses Prairie was set on fire by the Quinault Indian Nation for the first time since the 1800s. This 200-acre prairie is one fragment of the once more extensive coastal prairies found along the Olympic coast.

Lots of time, and many hands went into preparing the late-September burn. They set out a wide mow line, and laid out hundreds of feet of hose to support the burn. No engines or UTV’s were used, just bladder bags, flappers, and drip torches. Not as original as the friction fire burns that likely started the original fires on the prairie, but a far cry from the machine and technology heavy prescribed fires of modern times.

The burn was one project under the Washington Coast Restoration Initiative, a state-funded program created by The Nature Conservancy for communities on the coast to do on-the-ground work to improve land management. In the past, Quinault used fire to encourage desired plants and wildlife in the prairie landscape. With this project, they’re using traditional practices such as fire on Moses Prairie to improve production of berries, roots, bulbs and plants for basket-weaving materials, and stimulate the wetland prairie for wildlife such as ducks, geese, butterflies, bear and elk.

A group of us from the Center for Natural Lands Management traveled out to support their burn operations, and get the opportunity to burn a prairie completely different than the dry gravelly outwash prairies in the South Sound. As we circled up with the Quinault burn crew; tribal members, and elders, our boots wet as our weight began to make the ground seep, we shared and listened to stories about the place we were about to burn. The elders imparted the importance of communication. Communication is what allowed for us all to be there in that moment, having an intention to get something done, and listening, talking, and sharing a common vision. It was fitting words for what we were about to do.

Bob, our burn boss, brought a piece of pitch wood of longleaf pine, the foundation tree of the south, where he burns in the winter season. We used it to start the prescribed burn an old way; no burn mix, just fire and pitchy wood. It was a small gesture, bringing some of the fire from the south; where this history of ecological burning has been long and continuous. We hoped some of the flame of Southern fire would help again start a long legacy of fire that is the right of the people who have lived in these wet mossy forests and prairies the longest.

The fire itself was text-book and short; maybe an hour. We did our best to let everybody get an experience putting fire on the ground. The slough sedge and Labrador tea burned well, bog gentian and sundew remained flowering after the burn, the wet and boggy nature of Moses prairie gave us a gentle entry into burning this landscape again. Hopefully the elk will again forage in the new growth in a few weeks. The steady coastal winds made ignitions feel mostly like sailing. The smoke came together and went up high and into the upper winds. Everybody was smiling.

For many from the Quinault crew it was their first or second prescribed burn, and the feeling of joy was palpable when we again circled up at the end of the burn. Fire is one of the quickest ways to bring people together. For us at CNLM we get the privilege to burn almost every day in the summer, and many of has have been for many years. The opportunity to again feel the excitement of burning for the first time was a great gift to receive and share.

And helping to peel back a layer of colonization that happened on this landscape, while small, made it all the more potent.

The Nature Conservancy created the Washington Coast Restoration Initiative and supports it in the Legislature. We work with the Quinault Indian Nation and Center for Natural Lands Management on many projects.

Putting Fire to Work in Washington

Photographed by John Marshall

Eastern Washington’s dry forests have evolved with and depend on regular, low-intensity fire to thrive.

Washington's recent string of record-breaking wildfire seasons is spurring a call to action to develop and implement an overarching strategy to restore healthy forests that are resilient to routine, low-intensity wildfires.

To protect communities and timber resources, we have been aggressively suppressing wildfire for over 100 years, and today, large portions of our forests are unnaturally dense with high levels of forest fuels, and less able to resist insects, disease and severe fire. When wildfire does break out, these unhealthy forest conditions increase the likelihood of catastrophic fires that threaten lives and homes.

One tool in restoring forests to be more resilient to this kind of fire is the use of controlled burns, or prescribed fire, to reduce the fuel load and return forests to a more natural fire cycle.

In the spring of 2016, the Washington State Legislature passed House Bill 2928, the Forest Resiliency Burning Pilot project. This pilot is examining the role of controlled burns in creating healthier, more resilient forests.

More details about the project are here: Put Fire to Work

The Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest is working with partners now to implement a series of controlled burns across about 8,000 acres under the pilot project. The Conservancy is supporting this work. Participants in this pilot include the Washington Department of Natural Resources, Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, Tapash Sustainable Forest Collaborative, North Central Washington Forest Health Collaborative, Northeast Washington Forestry Coalition, and Washington Prescribed Fire Council.

Controlled Burn on Yellow Island

Photos & video by Chris Teren

The Nature Conservancy’s Yellow Island lies between Orcas and San Juan Islands in the Puget Sound. For the last 30 years, this 11-acre island has been the site of extensive research and repeated controlled burning to help maintain the diversity of species that require frequent fires to survive in healthy Puget Sound prairies.

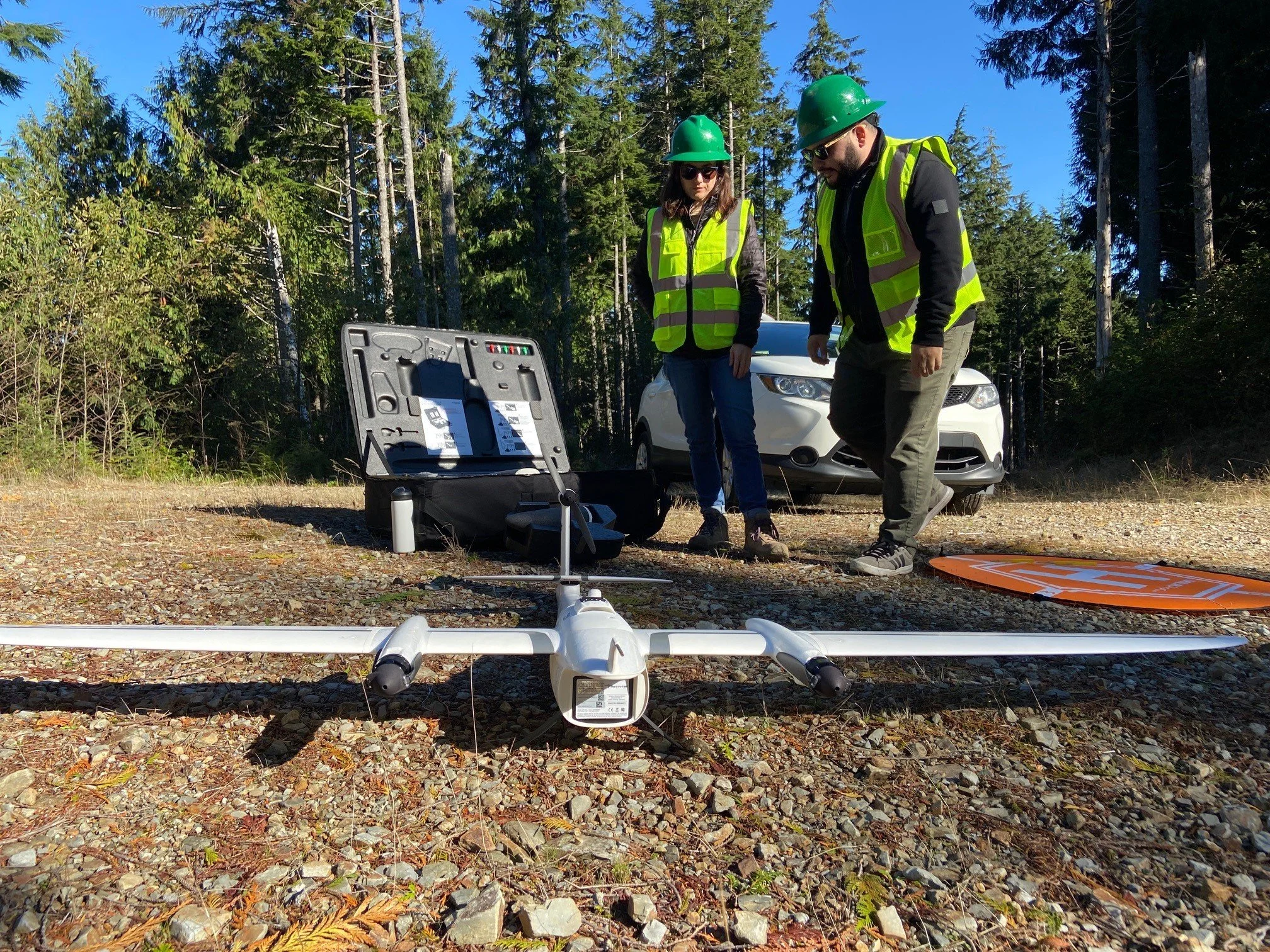

This year, for the first time, we had a new dimension to this ongoing research. Volunteer Chris Teren brought in his drone photography and video skills to help document the burn. Watch his drone video below.

It’s important to note that Chris worked closely with our team, including Island steward Phil Green and the fire team from Center for Natural Lands Management, to safely document this event. Drones have posed real safety hazards to crews fighting wildfires and house fires in Washington, and no one should ever send a drone in to a fire when it’s not part of a planned exercise.