Using dynamite for restoration may seem like a paradox, but at TNC’s Port Susan Bay Preserve, we explored dynamite as a way to create estuary channels. The inspiration behind this method was to see if explosives could reduce the ecological impact of channel creation in comparison to using heavy machinery.

Port Susan Bay Preserve: Where have all the Chinook Gone? (Part 1)

Where the Water Meets the Sea

KCTS9-Crosscut interviews Dr. Emily Howe, Aquatic Ecologist at The Nature Conservancy for their “Human Elements” series where Emily talks about her personal connection to marshes and how she is working to restore these unique—and messy—ecosystems.

Do you have launching toe? Probably not, unless you’re a levee!

Rebuilding an Estuary, Designed by Nature

Written by Beth Geiger, Northwest Writer

Graphics by Erica Simek-Sloniker, Visual Communications

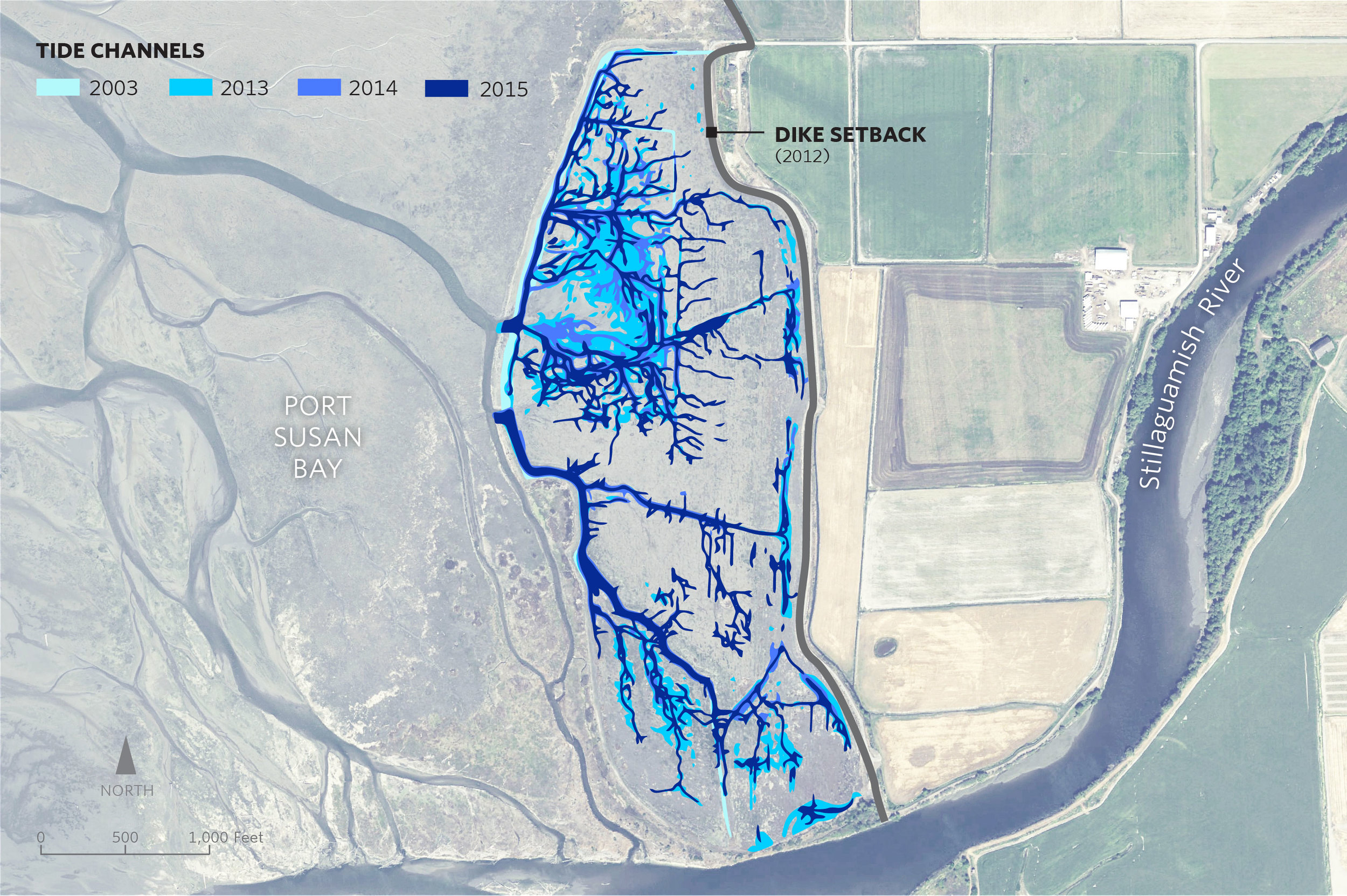

A dramatic change has taken place in a marsh in Port Susan Bay, near Stanwood, Washington. In just three years the total length of tidal channels naturally increased tenfold, from 2,300 to 23,000 meters.

Tidal channels are key to a well-functioning estuarine ecosystem. Channels increase habitat diversity, which in turn increases species diversity. Juvenile salmon use the channels, dabbling ducks use them, and invertebrates that provide food for other species use them.

Scientists like Roger Fuller, an ecosystems ecologist at Western Washington University, are chronicling the new tidal channels, along with other changes here. Fuller says the development of so many new channels is “a big surprise.”

Marsh Revival

The new channels started forming in 2012, after The Nature Conservancy removed 7,000 feet of dike that had separated the 150-acre marsh from the rest of Port Susan Bay since the 1950s. The dike removed had over time diverted Hatt Slough, the Stillaguamish River’s biggest distributary channel, south where it spills into Port Susan Bay. That dike had also cut the marsh off from its main source of fresh water and sediment.

With marsh, river, and Puget Sound connected again, natural processes took over. Critical estuary habitat quickly began to be rebuilt. A natural revival was underway.

The channels are a big part of this revival. “Channels build connections, creating the intimate links that tie the marsh, tide and river together,” Fuller explains. “They serve as the trade routes of the estuary, funneling water, sediment, fish, and the organic matter that fuels the entire estuarine food web back and forth between marsh and tidal flat.”

Sound Science

Supported by the Conservancy, Fuller and other scientists including Greg Hood with the Skagit River System Cooperative, and Eric Grossman, Christopher A. Curran and Isa Woo from the United States Geological Survey have been studying the channels and other ways that this estuary is recovering.

The researchers analyze before and after data, and compare the restoration area to a nearby reference marsh which has never been diked. They measure suspended sediment, water temperature, salinity, current, as well as topographic and ecological changes.

New tidal channels aren’t the only “before and after” they’ve seen. When the dikes were in place, the area inside them had been starved of its natural influx of sediment from the Stillaguamish River. The estuary had subsided until it was a meter lower than the surrounding tidelands in some places. It functioned more like a pond than a dynamic estuary. For example, there was no access or protected estuarine habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon transitioning from the Stillaguamish River into Puget Sound.

With the dike removed scientists have recorded a measurable rise in the height of the marsh. During those years the sediment delivered to PSB was unusually high in part due to the March 2014 Oso landslide. However, the data suggest that even if the marsh gets half as much sediment in future years, it may still rise fast enough to keep up with the rising sea level, estimated to be an average of about 24 inches by 2100.

Lessons from Nature

Fuller says that being surprised by nature here isn’t all that unexpected. “The one thing I knew before the restoration was that I would be surprised by the changes triggered by the restoration,” he says. “There's been so little research on restoration in northwest estuaries that I knew it would be really interesting to watch it unfold.”

The restoration project is part of the Port Susan Bay Preserve, which includes 4,122 acres of estuary that the Conservancy acquired in 2001. The science being conducted here reaches much further than the Preserve itself. Along with learning new lessons, we are applying scientific concepts and models honed under this and other Conservancy projects such as Fisher Slough.

Together, these projects demonstrate that carefully planned restoration can have complementary, not conflicting, benefits for people, salmon, farms, and wildlife. The Conservancy-led Floodplains by Design provides the partnerships and funding that ensure these lessons can extend to restoration projects all over Puget Sound.

As a result of diligent science and critical partnerships like this, we are learning how to make Puget Sound more resilient as climate changes, and sea level rises.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK IN PUGET SOUND

LEARN HOW CLIMATE CHANGE WILL AFFECT THE REGION AND WHAT WE'RE DOING TO ADAPT

Livingston Bay: Remodeled by Nature

Written by Joelene Boyd Puget Sound Stewardship Coordinator /Interim Stewardship Director

Maps by Erica Simek Sloniker, GIS & Visual Communications

Three years later the change is remarkable! Wood has moved out of the pocket estuary, the channel network is expanding and a natural sand spit is forming.

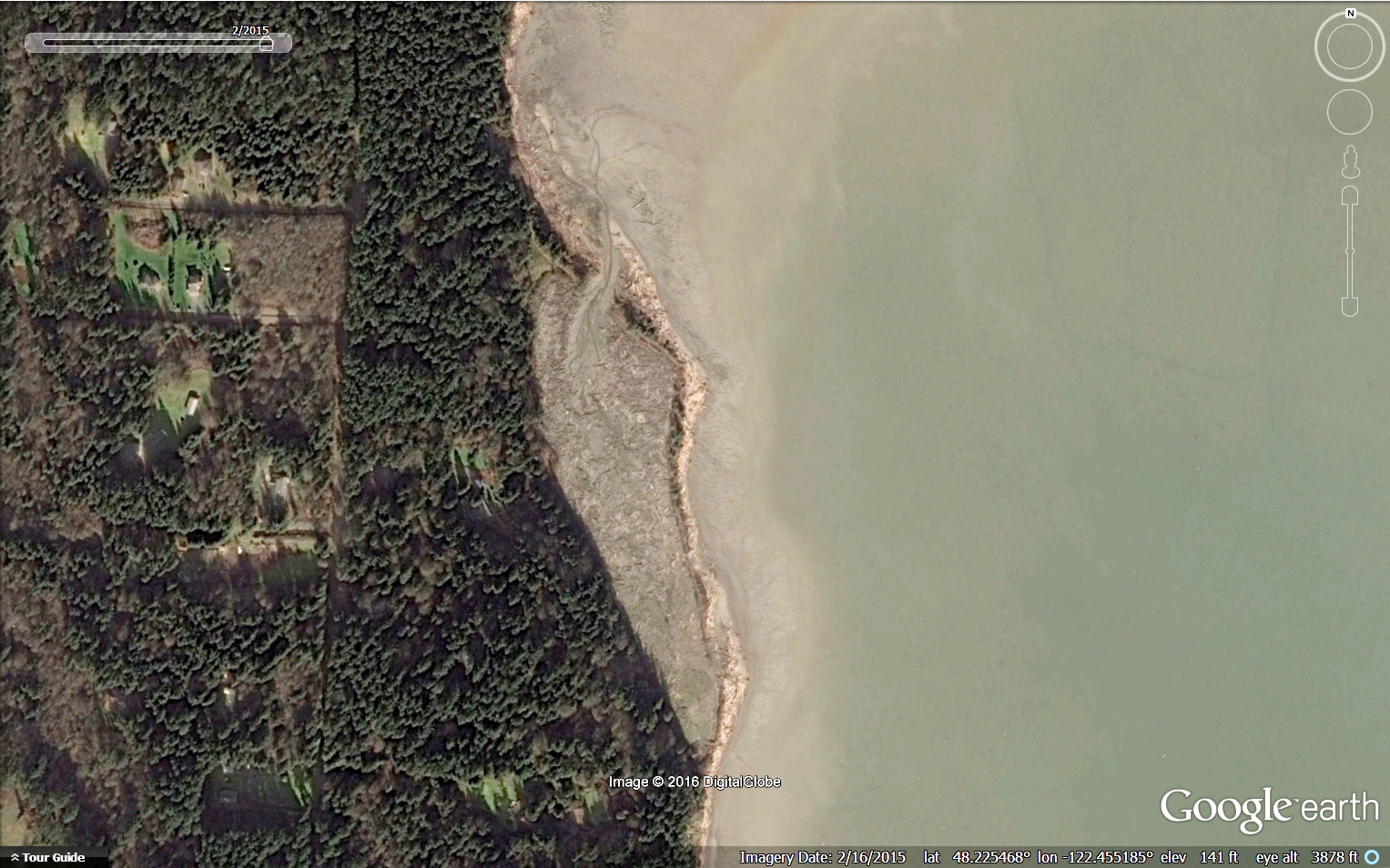

In 2012 The Nature Conservancy set work to restore a 10 acre pocket estuary in Livingston Bay. In order to do this we hired contractors to repair the breach at the southern end of the pocket estuary, breach the dike on the north end and excavate a “starter” channel so that tidal exchange would return. The desire was for wood to be carried out of the site by wind and tides and a channel would grow. The major goals of the project were to restore tidal influence to the pocket estuary, improve access for juvenile salmonids and other fish and restore salt marsh habitat.

From aerial images we see that this is exactly what’s happened - wood is moving out of the site through this starter channel allowing a network of channels and salmon habitat to develop. Additionally the natural sand spit is continuing to extend. It is impressive to see nature’s forces working to restore this pocket estuary with a little helping hand.

A pocket estuary is a type of nearshore habitat that is used to describe an estuary that is protected from waves, wind and other forces. Pocket estuaries in Puget Sound provide critical rearing habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon and other fishes that depend on these partially enclosed estuaries to eat, grow and seek refuge from predators. Researchers estimate that in the Whidbey Basin approximately 80% of the pocket estuaries have been lost.

Historically the Livingston Bay pocket estuary had been diked in the early 20th century to allow for grazing. However, sometime in the 1980s a storm had breached the southern end of the dike causing the area to fill up with wood from strong winter windstorms and high tides. After purchasing the property the Conservancy set to work on designing and carrying out a restoration project to restore the daily tides and function of the pocket estuary necessary to provide juvenile Chinook habitat which was identified as a limiting factor for Chinook salmon survival (Beamer 2003).

Learn More About Our Work in Puget Sound

Timelapse: Port Susan Bay Shorebirds

Video by Joelene Boyd, Puget Sound Stewardship Coordinator /Interim Stewardship Director

A timelapse camera was set up at our Port Susan Bay Preserve in an attempt to capture the King Tides. We ended up getting so much more, see what our cameras captured in the video above!

Learn more about our work at Port Susan Bay

Oyster Love: All the Ways They Benefit Us

Created by Erica Simek Sloniker, Visual Communications

Oysters are filter feeders. An adult oyster can filter 25 gallons or more of water per day in search of food. In doing so, they filter algae from the water, reducing nutrient loads and keep bay water clear so that eelgrass and other marine life can thrive.

More oysters equal cleaner water for everyone. Fewer oysters means our bays and estuaries are worse off. And if water is too polluted, the oysters living in it can be poisonous for us eat.

The Conservancy, shellfish growers, and other partners like the Puget Sound Restoration Fund and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife are working to restore wild, native oysters in the bays of Puget Sound.

LEARN HOW WE PROTECT OUR OYSTERS

Restoration Works: Seeing Success in Skagit, Stillaguamish and Snohomish Estuaries

Photographed by Leah Kintner, Puget Sound Partnership

Recently, we went out with the Puget Sound Partnership Leadership Council and the Salmon Recovery Funding Board for an informative day to tour restoration successes throughout north Puget Sound.

The group joined Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife's Jenna Friebel and Belinda Rotton, Skagit County Commissioner Ron Wesen and Skagit Watershed Council's Richard Brocksmith to tour WDFW's Fir Island Farm estuary restoration project. We then headed to the Stillaguamish Dept of Natural Resources office for an overview of the Stillaguamish watershed by Jason Griffith (Stillaguamish Tribe) and Kit Crump (Stillaguamish Lead Entity). Afterwards, the group toured Port Susan Bay (with our Jenny Baker and Kat Morgan) and went to the Tulalip Hibulb Cultural Center for an overview of the Snohomish watershed presented by the Morgan Ruff and Kurt Nelson (Tulalip Tribe). At the end of it all we toured the recently completed Qwuloolt estuary restoration project with the Tulalip Tribe’s Morgan Ruff and Josh Meidav. It was a beautiful day touring 680 acres of estuary either restored or with restoration underway!

See photos from the day in the slideshow above.

Learn more about our work around Puget Sound.

Construction Progressing at Fir Island Farm

Conservation in action along the Skagit River

Written and Photographed by Jenny Baker, Senior Restoration Manager

Fir Island Farm estuary restoration is underway and the site is a hub of activity. Jenna Friebel, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Project Manager, reports:

“We are about half-way done with year-one construction. We are importing 4,200 tons of dike material, or 150-175 truck and trailer-loads, per day; and IMCO Construction has about 40 people working on-site 5-6 days per week.”

The project, which is located in the Skagit River delta west of Conway began earlier this summer and will continue through summer 2016, with funding from Puget Sound Partnership, NOAA, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and The Nature Conservancy (15 percent is federally funded).

This summer a setback dike, drainage infrastructure and marsh channels are being constructed. Next summer the existing dike will be removed restoring 130-acres of tidal marsh and channels, and opening up critical habitat for endangered juvenile chinook salmon! See the progress of the construction in the slideshow above:

The first step in constructing the new setback dike is to strip away the sod. Seen in Photograph 1.

After stripping sod from the dike footprint, the construction company lays down a geotextile material and then places and compacts imported soil to form the dike. Seen in Photograph 2.

The setback dike is protected from wind and waves on the bay-side with fabric and rock, and then covered with soil. Later this summer it will be seeded with grass. Seen in Photograph 3.

Drainage is important to maintain the productivity of farmland on Fir Island. A pond was constructed to provide additional storage for water draining from Fir Island. From here the water will either drain out through new tidegates or be pumped out through a new pump station into the restored estuary. Seen in Photograph 4.

Learn more about our work on Puget Sound.