Parts of Cle Elum Ridge have been closed to recreational snowmobiles for the 2021-2022 season.

Unmaking and Remaking History

Written & Photographed by David Ryan, Field Forester; Kyle Smith, Washington Forest Restoration Manager

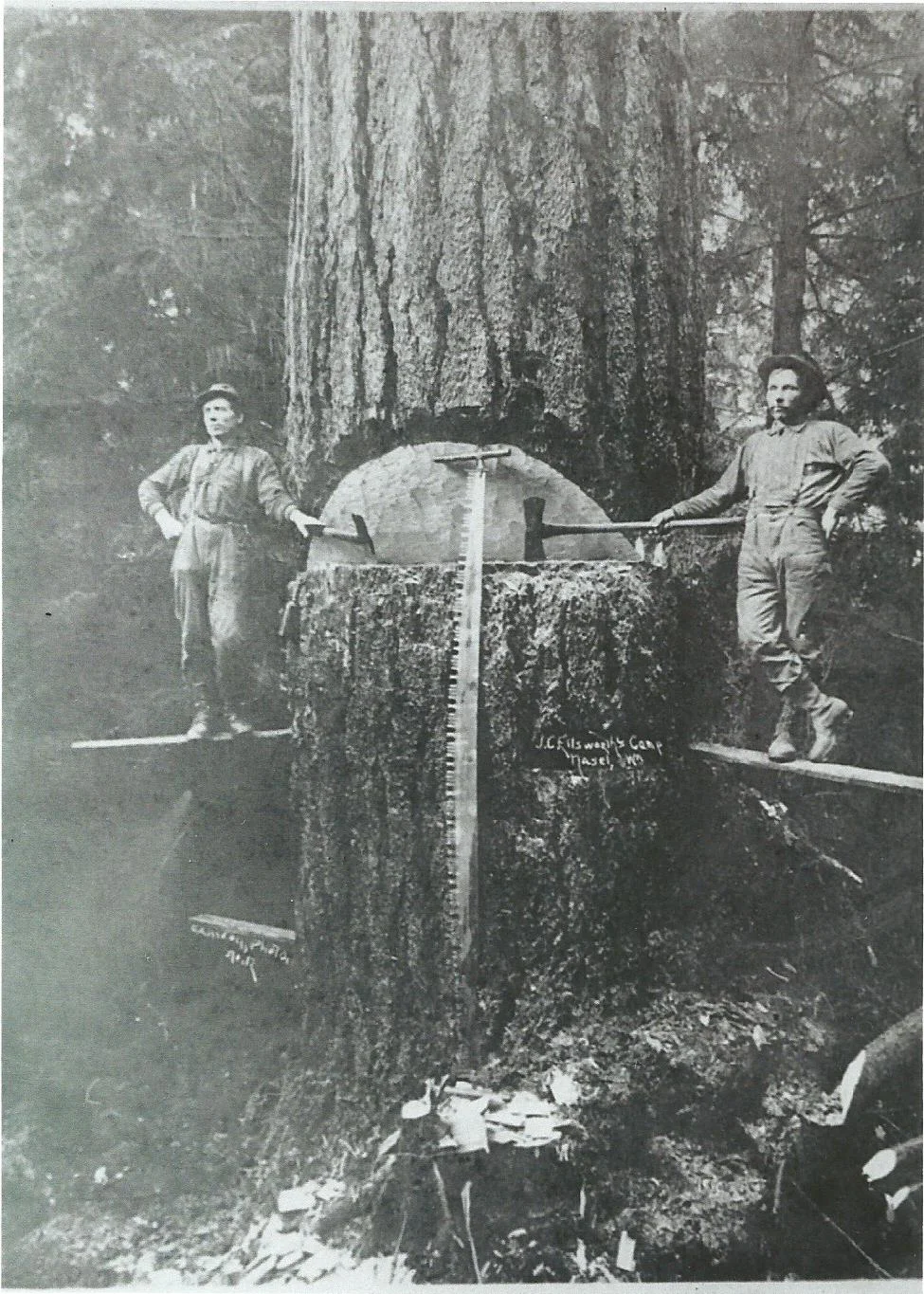

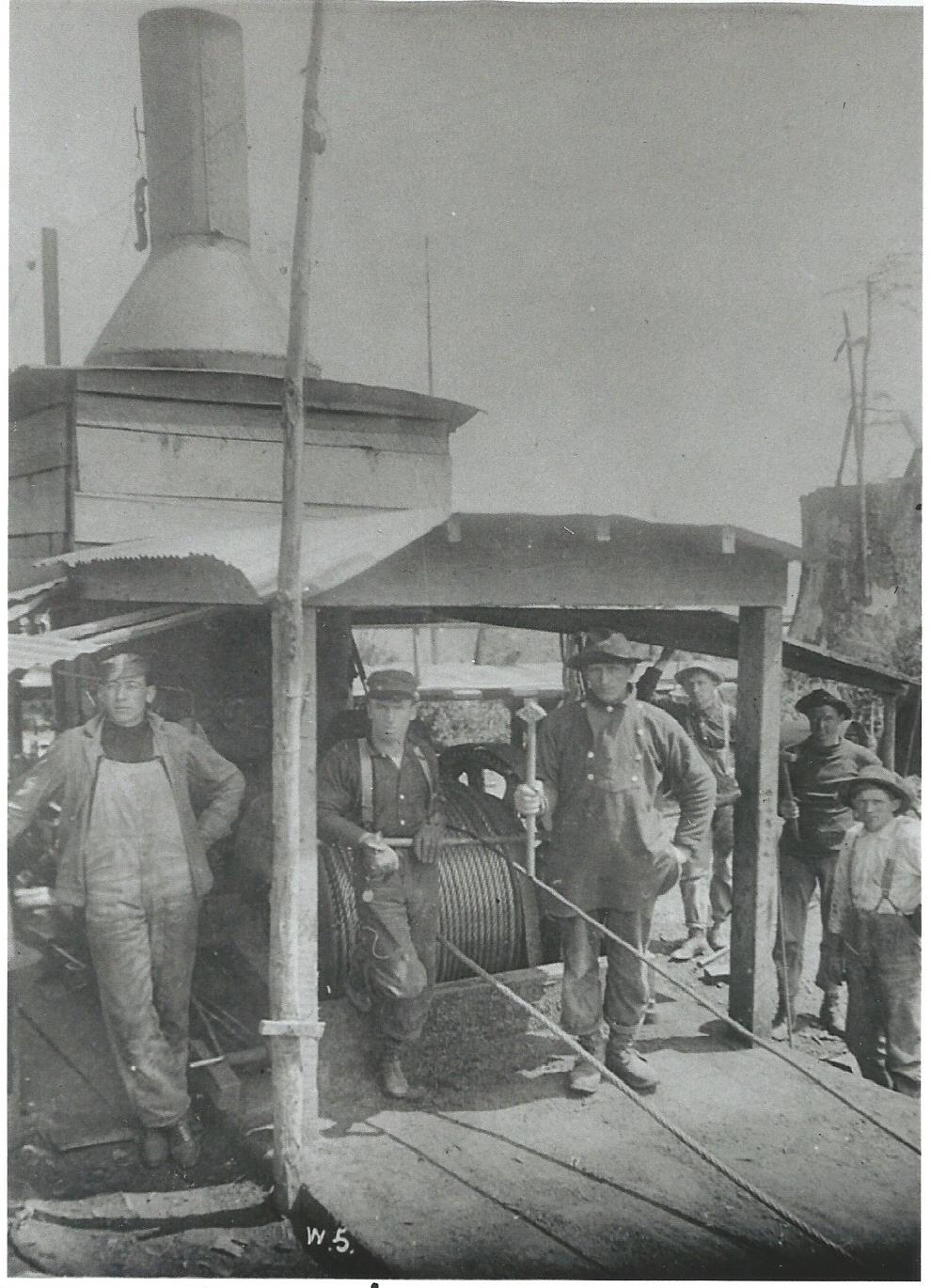

In the early 1940’s a cedar tree standing in the Ellsworth Creek watershed and measuring approximately 6 feet in diameter was felled by loggers from the Brix Logging Company. The bottom 110 feet of that tree was bucked into two 55 foot lengths and laid parallel on either side of Ellsworth Creek. Those two pieces formed the foundation for a bridge that spanned the creek until July 2016 when The Nature Conservancy, with the help of Ohrberg Excavation, removed that bridge, used the timbers to enhance stream structure, and restored the stream banks in an effort to improve our freshwater ecosystems and salmon habitat.

It was with mixed feelings that I watched this bridge retire from service. The design and materials were simple, efficient, and obviously effective. It was a tribute to ingenuity. Removing this bridge was necessary for many reasons; the environmental benefits are undeniable and, after over seven decades, its utility and integrity were eroding. Retiring this bridge from service supporting logging helps us to once again recruit Ellsworth Creek into service supporting salmon. But its history, and remembrance, are important. Not only was the bridge used to haul logs and loggers for almost 80 years, it was a remnant and a reminder of the history of the Pacific Northwest, of the men and women who resolutely toiled under arduous circumstances to help build this country. For better and for worse, these people worked the land and shaped it into what it is today. While some may debate about the logging history of the Pacific Northwest and the legacy that it left, I cannot dismiss the value of people who worked so hard under perilous conditions to achieve such monumental feats.

That same spirit and innovation, combined with modern machinery and technology, was apparent as the Ohrberg crew expertly removed the bridge, rebuilt the natural historic gradients, and decommissioned the road approaches as we unmade the human history and remade the natural history of Ellsworth Creek. The large diameter cedar that was used to make the bridge was returned to Ellsworth Creek in the form of a new log jam designed to foster salmon habitat. Given historic logging practices and “stream cleaning” activities from years past, it is unusual to be able to contribute wood of this size and type back into the system. When the work was completed my feelings were no longer mixed. Working with the crew, I experienced the same stalwart work ethic of those who built the bridge long ago; and I felt the absolute joy of seeing the namesake creek of this preserve take another positive step in our restoration goals.

At Ellsworth Creek Preserve we are striving to maintain and restore the forests and waters, we are striving to stay true to the natural history of the Willapa Hills. So that when salmon at sea answer the primordial call and resolutely undertake their own monumental feat of returning home to spawn, the home they return to looks like that of their ancestors who answered the same call long before there were roads and bridges in the neighborhood.

LEARN MORE ABOUT ELLSWORTH CREEK

Ellsworth Creek's Log Jam Extraordinaire

Written by Jeanine Stewart, volunteer writer

Think of a Chinese finger trap. Those little woven paper toys have one thing in common with a log jam: they tighten up with the application of outside force.

This is the type of contraption our Willapa Area Forester David Ryan is helping to install 47 times over down a one-mile stretch of Ellsworth Creek.

It’s part of the Ellsworth Creek restoration project – a major component of our overall restoration strategy for the 8,100 acre Ellsworth Creek Preserve.

The plan may sound like a head scratcher. After all, could there possibly be environmental benefit from jamming up certain points in the river with logs? The short answer is yes.

For one, log jams restore complex structure to the ecosystem in this section of the river. Literally and figuratively, these logjams provide a cascade of many benefits that help rehabilitate the watershed.

Decades ago, people engaged in what they termed “stream cleaning” – getting rid of the wood in the water – in an effort to improve the salmon habitat, Ryan says. He adds this backwards thinking created an oversimplified and more sterile riverine habitat. The salmon need the wood in the water to foster spawning habitat, security structure and also for nutrient cycling.

The log jams also re-engage floodplains – that area of low-lying ground adjacent to the river – in order to restore the habitat. This is important since floodplains create productive forests, store and filter water for streams and create a complex stream structure, which supports larger and more diverse fish populations. In return, healthy salmon populations help return nutrients to the forests as they complete their life cycle.

But for Ryan, there are far more benefits than simply the outcome of this project. For him, the beauty lies in the journey.

He gets up every morning knowing he's about to head out into the wilderness, into the thick of the forest along Ellsworth Creek, to direct the installation of these log jams. Each of the 172 trees he’ll have installed by September takes anywhere from 10 minutes to one hour, as each presents its own unique problem to solve.

"It's so much fun and it's so out of the box," he says, "because the intent of the project was pretty extensive, as the engineer said this was the rehabilitation of an entire system. So right there, when you look at it from that perspective, that's out of the box."

Similar projects of this sort will start with one, or maybe up to three log jams. He's already done over 30 and is well on his way to completion of all 47 by September, all using trees that were already scheduled to be felled as part of our other work on the preserve.

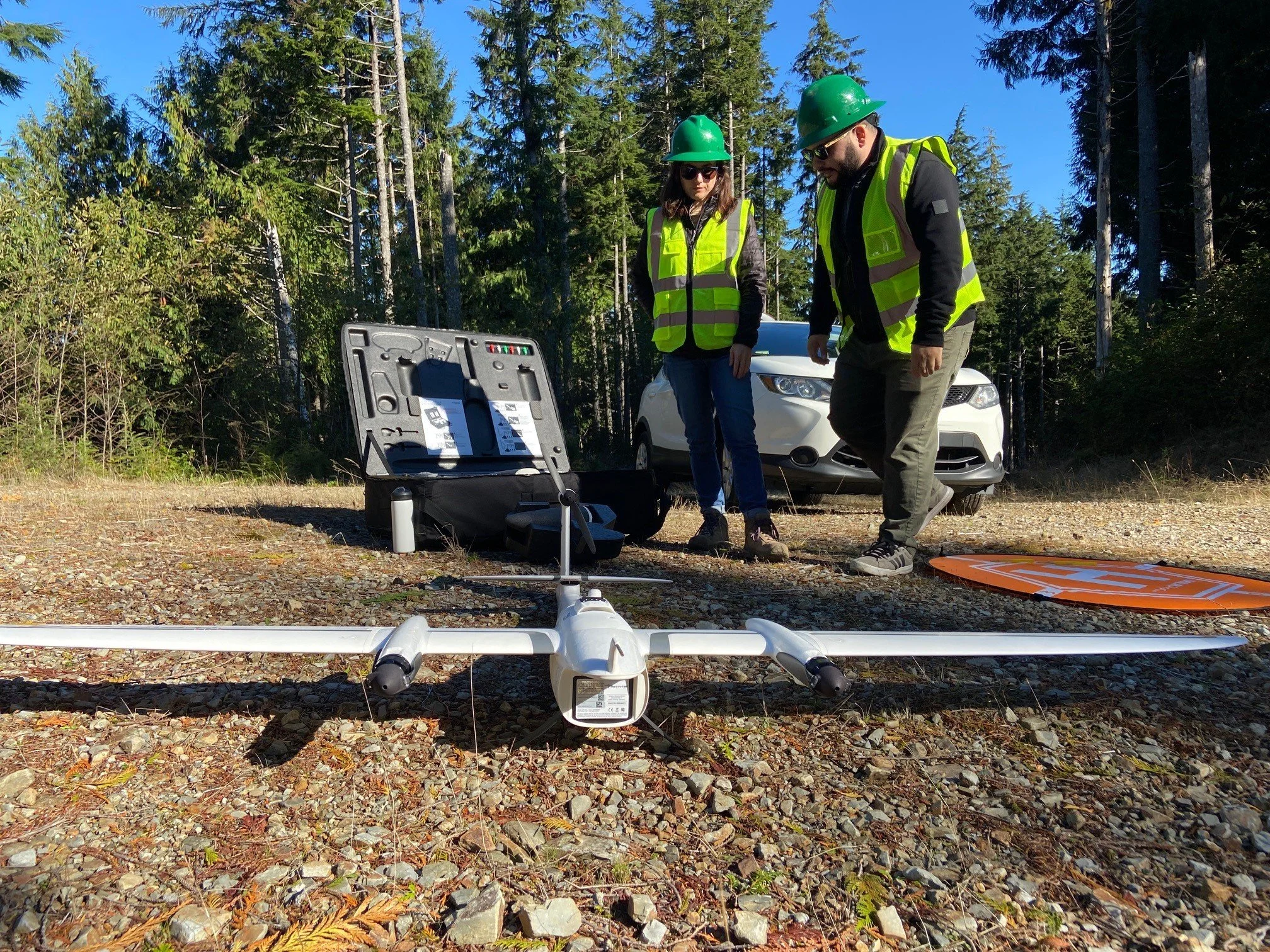

Ryan helps direct the process of cutting the trees down and then placing them in the water by lowering them, via lines attached to cranes, into the stream. This means relaying plans to the loggers and ensuring that when the cranes lift the logs up and then lower them into the streams, they land in the correct place. Besides the excitement of the sheer magnitude of this project, the capabilities, dedication and hard work of the people Ryan works with are a major part of the thrill for him. That includes Natural Systems Designs and its engineer Mike Hravocek, who surveyed the stream and drew up the plans; as well as White & Zumstein, who have been contracted to do both the logging and the installation.

“From the landing to the creek, the sawyers, equipment operators, chasers, and rigging crew worked hard in a challenging environment and not only did a great job with the logjams but the logging as well,” he explains. “The rigging crew was particularly noteworthy for their ability to understand the purpose of each design and make those designs manifest on the ground as they were drawn up and intended. The whole crew understands the physical forces at work, has a positive attitude and is very mindful, which makes me feel a lot safer on site and makes compliance a lot easier. And their innovative approach to using heavy equipment for a different purpose makes this project a lot of fun to be part of.”

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK AT ELLSWORTH CREEK

From the Field: Log jams at Ellsworth Creek

Video by David Ryan, Field Forester

Check out this video from the field showcasing how we construct log jams!

In the late 1970's and early 1980's, many northwest streams were completely logged - log jams restore the woody debris salmon need. This project helps reach our restoration goals for the nearly 10,000 acres of Olympic land and water we protect.

Learn more about our work at Ellsworth Creek

The Conversations & Community at Ellsworth Creek

Written by David Ryan, Field Forester

Photographed by Larry Workman, Quinault Indian Nation

We are standing in a creek bottom with water around our feet. It’s raining. It’s cool, but not too uncomfortable. As the old saying goes: “There’s no such thing as bad weather; just bad clothing.” I am fortunate that my guests seem to understand that. My guests are several members of the Quinault Nation and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

They are here to look at the work we are doing at Ellsworth Creek Preserve. This year we have decommissioned roads, upgraded roads, implemented a forest restoration thinning, and worked on an in-stream restoration … among other things.

As a field forester for The Nature Conservancy one of my duties is to participate in meetings, tours, and workshops pertaining to forestry and ecology. I thoroughly enjoy when those events are held at Ellsworth Creek. I love meeting people who are interested enough to visit and look at the forest and I always learn every time guests arrive.

As a temperate, coastal rainforest Ellsworth can be a challenging place to visit. It is steep. It is brushy. It is wet. Those logistical challenges increase when coupled with management activities on the landscape. Again, I am fortunate that my current guests understand that as well. They are game for inclement weather, rough ground to walk over, and heavy machinery to coordinate around.

The rewards are rich. We visit log jams installed this summer that are already re-engaging historic floodplains and channels. We look at forest stands that were recently managed, historically managed, and others that will not see human management again. We checked roads that no longer exist due to our work. And most importantly, we talk. We discuss. We question. We answer… or we don’t. We think critically. We don’t always agree. One course of action here may or may not work for other land managers elsewhere. But the discourse is always respectful. And we all seem to enjoy the conversation.

We have now spent many hours walking, talking, and wending our way through the rain and the woods; certainly a physically uncomfortable day for many people. Eventually a discussion arises of whether people want to continue downstream to look at some bigger log jams and another forest stand treatment or go back and get warm and dry. I hear a colleague call out for “a coalition of the willing to venture further downstream” to continue the discussion.

Almost everyone walks downstream. The conversation continues. I am grateful when people take the effort to really look at our work. I am grateful for my guests. And this place.

Back to the Future of Our Forests

Photographed by Nathan Hadley, Northwest Photographer

We recently went to our project in Oak Creek to restore the forest to health, prior to the advent of wildfire suppression efforts. We've partnered with the Department of Fish and Wildlife, Yakama Nation and the U.S. Forest Service to thin brush and cut trees for timber to pay for most of the project. Some of the trees end up on creeks and rivers. They help sediment build up and restore fish habitat, also lost with wildfire suppression. This project is also a great opportunity to provide the local community with work and renewed habitat for wildlife. See photos from the day in the slideshow above!

Learn how we protect our forests.

Help us restore our forests for nature and people.

BRINGING BACK WILD SALMON

Bringing Back Wild Salmon

Photos and Video Recording by Kyle Smith, Washington Forest Manager

Video by Cailin Mackenzie, Globe Intern

Narration by Lauren Miheli, Volunteer Coordinator

The Nature Conservancy worked with the Quinault Indian Nation and other partners to install six engineered log jams on a tributary of the Clearwater River. Kyle Smith, our Forest Manager, relocated fish from the stream to protect them during construction. In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, many northwest streams were completely logged – log jams restore the woody debris salmon need. This project helps reach our restoration goals for the nearly 10,000 acres of Olympic land and water we protect.