As 2022 comes to a close and we look ahead to 2023, our State Director Mike Stevens shares his reflections and what will shape our work as we move forward.

The Conservation Futures Promise

Vote for Nature

William D. Ruckelshaus - a true environmental champion

We at The Nature Conservancy have just learned of the passing of William D. Ruckelshaus, a longtime advisor and a true environmental champion for many decades.

Bill Ruckelshaus was founding administrator of the federal Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, given the mission to enforce the nation’s new Clean Air and Clean Water acts. He undertook enforcement actions against big industrial polluters and severely polluted cities, set health-based standards for air pollutants and standards for automobile emissions, and banned the general use of the pesticide DDT.

Here in the Northwest, he had the vision for a collaborative, science-based effort to restore Puget Sound that led to the development of the Puget Sound Partnership, which he led from its founding in 2006 until 2010. He remained active and involved in the affairs of the nation and of Washington state, joining us at the March for Science in 2017 and co-authoring, with Sally Jewell, an op-ed for The Seattle Times in support of Initiative 1631, a measure to reduce climate change, in 2018.

Meet Our New Director of Conservation, James Schroeder!

Renewing My “beLEAF” in the Future of Conservation

Hope Persists for Pygmy Rabbits Despite Blaze

We're honored to be a 'Conservation Partner of the Year'

Written by Heather Cole

Puget Sound community relations manager for The Nature Conservancy Washington Chapter

A blissful night of smiles, awards, good food and inspiring words was the theme last Thursday for the Snohomish Conservation District 75th Anniversary Better Ground Showcase. Inside the Mukilteo Rosehill community center, which overlooks Puget Sound, were the Snohomish Conservation District’s (SCD) closest 250 friends, partners and leaders — all have contributed to improving the Puget Sound region through sustainable actions that conserve land, water, forests and wildlife.

Over the past 75 years, the SCD has worked with thousands of stakeholders — from apartment dwellers to commercial farmers to everyone in between. The turnout for the event was evidence of the SCD’s quality of work, the community trust it has built and its future vision to innovate and push the status quo.

Jessie Israel, our Puget Sound conservation director, was honored to accept TNC’s “Conservation Partner of the Year” award. Monte Marti, event host and the SCD's district manager, explained the reasoning for this non-traditional honor and partnership: “The Nature Conservancy has taken a very unique and creative approach to advance numerous place-based conservation projects and initiatives in Puget Sound. They have recognized the value and need for local place-based activities and the critical role of local partners and champions. They have demonstrated that it is more valuable to support and guide than to impose their will on a local effort. This type of approach takes a unique style of leadership and a tremendous amount a courage, patience and listening.”

Other notable awards that were presented at the event were: Boeing as “Conservation Business of the Year," Ron Shultz, of the Washington State Conservation Commission, as another “Conservation Partner of the Year," TNC board member Greg Moga and organic farmer and local leader Tristan Klesick as “Conservation Leaders of the Year."

This night was not only about the awards; it also gave us a glimpse of the local young leaders who are doing outstanding work in the field of conservation. Lorenzo Rohani, a 17-year-old high-school student, captured our hearts with his keynote address on birds. (I also later learned that he published his first book on backyard birds at age 13!)

The things all 250 people had in common on this night were the passion and fortitude to carry this important work forward for another 75 years.

Thank you to the Snohomish Conservation District for creating an inspiring and wonderful night!

Fall Reflections

Written By Phil Levin, Conservancy Lead Scientist

The softening gray sky; cornflower yellow leaves piled up and smelling of their earthly past; once brilliant sockeye salmon carcasses collecting in swirling waters. Fall is in the air. I can feel it.

After a too-short Northwest summer, the twilight of autumn envelopes me and draws me inside.

For many, the onset of autumn’s north winds signals an end. A time to preserve the bounty of the summer; a time to prepare for winter’s rest; a season to dream of spring’s awakening. For me, though, it’s a beginning.

As fall sets in, I walk through my garden, assessing which plants thrived and which ones disappointed. Did I choose the wrong varieties? Was the soil deficient in some nutrient? Did the slugs take more than their fair share? Answering these questions is the start of next year’s growth and productivity.

Autumn is also the time I take stock of myself. I look back at the last year--what I have done well and where have I missed the mark. Am I the person I really wish to be? How can I grow to better father, partner, friend -- person? The equinox is the annual moment I begin again.

Self-reflection is also critically important for the science underlying conservation. Conservation science has been called a crisis discipline. As we confront climate change, acidifying oceans, rapidly altering ecosystems, extinctions, and the loss of biodiversity, we lack the luxury of time. Species are going extinct before they have the chance to be recognized by science, while fewer and fewer places around the globe support functioning ecosystems. In the words of the 16th century poet and Rabbi, Eleazar Azikri, “the time [to act] is now; rush; be quick; be bold.”

The urgency of the moment requires unflinching action, but as we consider what strategies will best address the challenges confronting the earth’s biosphere, we face incredible scientific uncertainty.

Taking actions under uncertainty requires an adaptive approach to management. This means that we must take action without precisely knowing the outcomes. Instead, we must define the potential risks and benefits of alternative solutions and identify vulnerabilities to key uncertainties. We can then identify the actions that we think are most robust to uncertainty.

The “adaptive” in adaptive management means that we carefully monitor and assess ecosystems so that our knowledge of the world’s ecosystems is improved and we learn how they respond to our actions. In this sense, repairing our world and growing our knowledge is not so different than my own autumnal introspection—we must take the time to reflect on our actions, determine if we missed the mark, and when necessary adapt our strategies to enhance our opportunities for success.

But when we do not stop and ponder our actions and assess how we are doing, success will be difficult. Surprisingly, conservationists often do not monitor their actions. For example, Steve Katz, a scientist at Washington State University, and his colleagues examined 23,123 examples of river restoration projects throughout the Pacific Northwest. Only 1569 of these projects-6.7 %- monitored the outcomes of their actions. In 93% of cases, conservationists lacked the ability to take stock, assess how riverine environments were doing, and if necessary, adjust and improve their actions.

For two decades, The Nature Conservancy’s work has been grounded in the tenets of adaptive management by a framework we call Conservation by Design. Conservation by Design provides a consistent, science-based approach with cutting-edge analytical methods. It has guided us in identifying what to conserve and how to conserve it. And, importantly we monitor and evaluate our work, and when necessary adapt our approaches to achieve better outcomes for both nature and people.

While there is no question that we must move boldly forward to tackle today’s challenges, autumn’s golden light reminds us of the importance of reflection. The Hasidic Rabbi Sholem Noach Berezovsky teaches that a person is like an aging house— to truly improve, one needs to be prepared to entirely destroy the structure of the old house in order to build a deep and strong foundation for an entirely new building. This lesson in no less important for conservation. While we may not need to demolish our house, we conservation scientists and practitioners must pause, reflect on our actions, and, if necessary, be willing to at least do a little remodeling. In doing so, we have the best chance to conserve and protect nature today and into the future.

G-I-Yes! Musings Among two Geographers on GIS Day

by Erica Simek Sloniker, GIS and Visual Communications and Jamie Robertson, Spatial Analyst

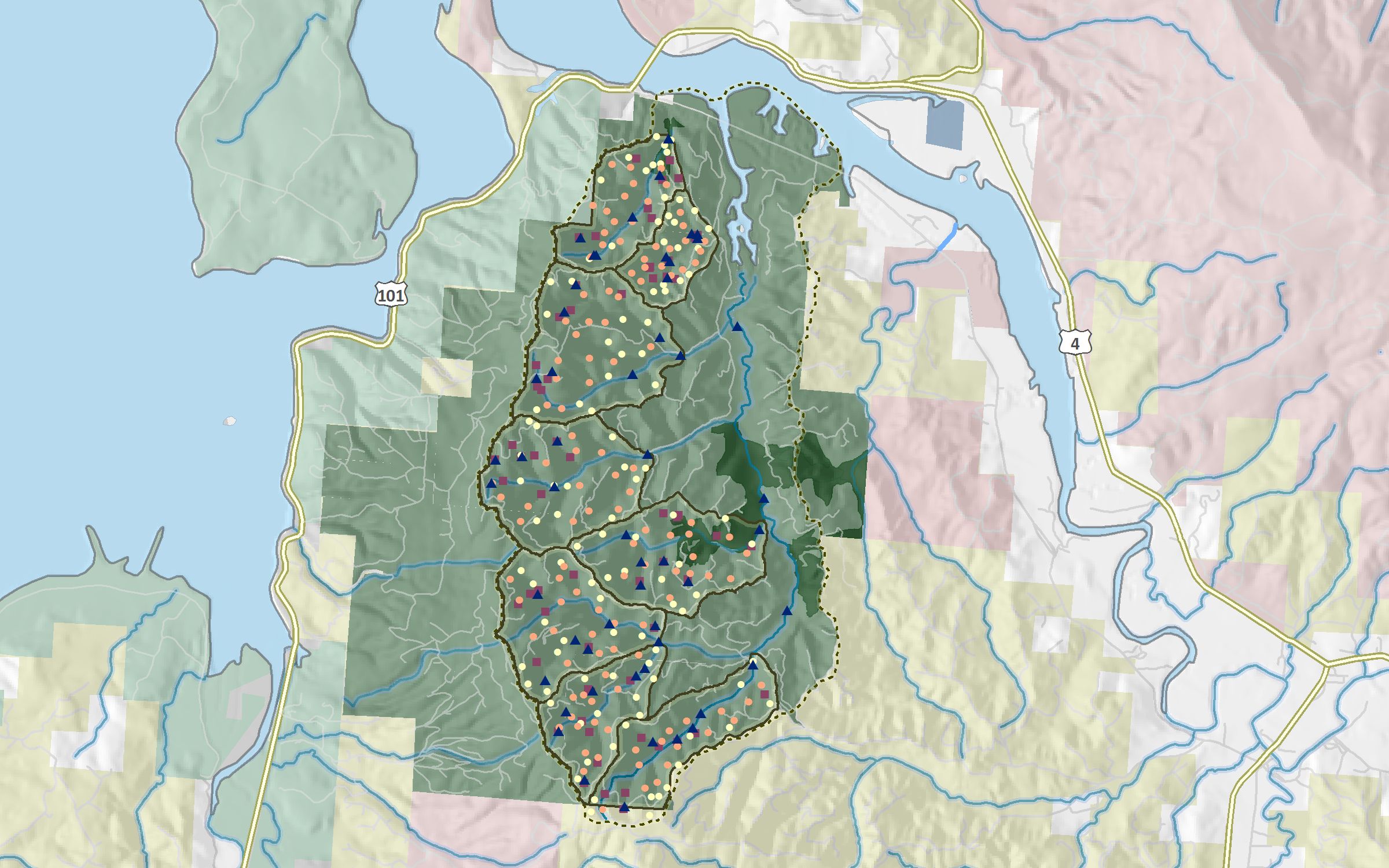

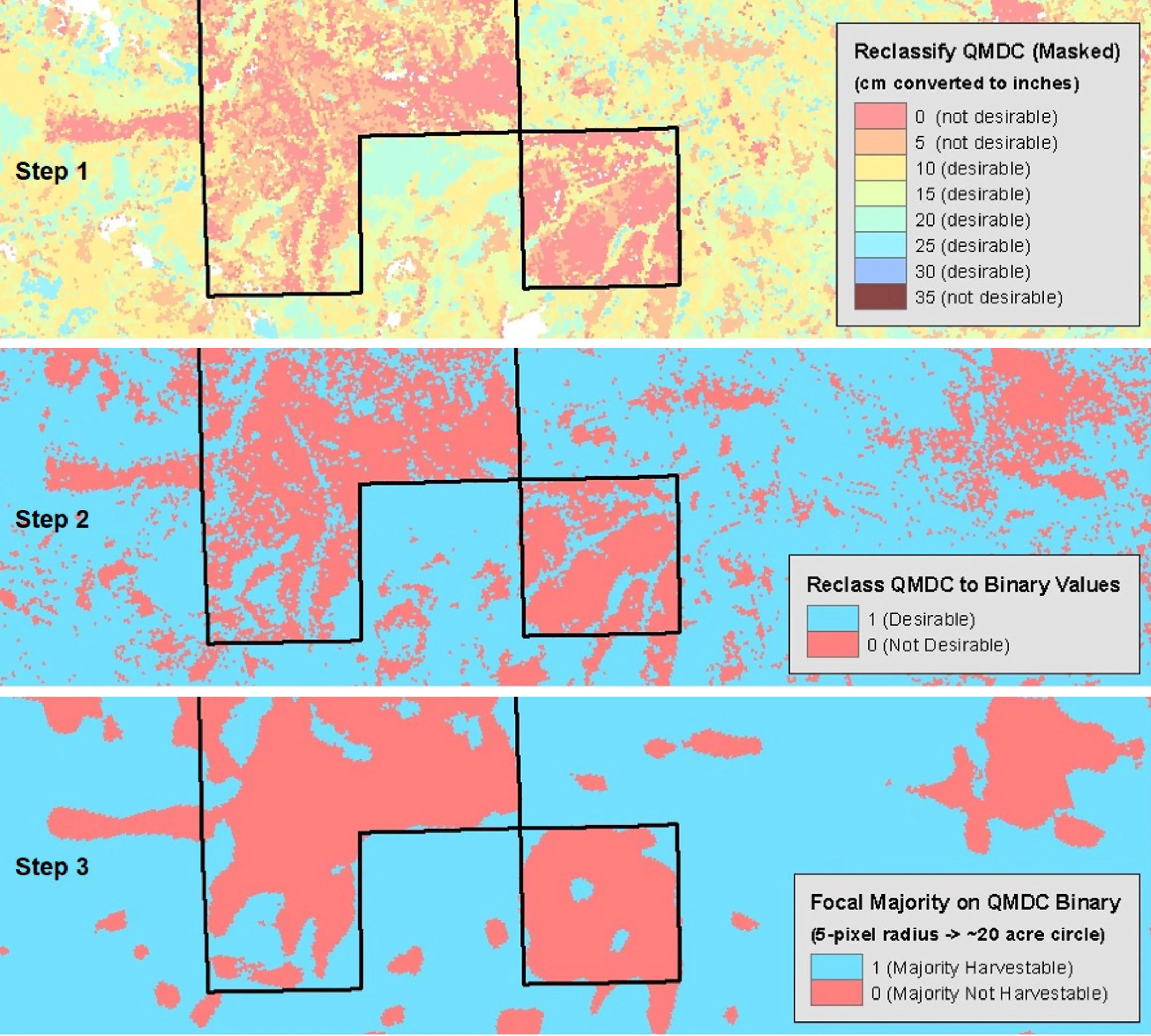

What low laying areas in this valley will flood during the next big storm? How many acres of Cascade forests need to be restored in order to prevent big, catastrophic wildfires? Where are the best elk migration corridors in our state?

These questions, and many more, can be answered using geographic informative systems (GIS). GIS is a computer system capable of holding and using data describing places on earth’s surface. It is a powerful tool that allows us to look at the relationships of features on the landscape. With that knowledge, we can make informed decisions about the places and things we care about. Cool! Companies like Google and Microsoft have harnessed the power of GIS in tools like Google Earth, Google Maps, and Bing Maps. Federal and state agencies use GIS to catalog and analyze information from natural resources to census track data. And non-profits, like The Nature Conservancy, use GIS to help solve the toughest environmental questions of the day.

In celebration of GIS Day, November 16th, a day that celebrates the real-world applications of GIS that are making a difference in our society, two GIS professionals from our office sat down for a question and answer session to talk maps and data and to share geography stories. They invite us all to become map lovers!

Q: What is a favorite GIS project you’ve worked on recently?

A (Jamie): An advantage to being a geographer at The Nature Conservancy is that we get to work on so many really cool projects! I’m really excited about stormwater modeling, mapping fire severity throughout the Pacific Northwest, producing numbers to help finance a timber mill project, and modelling coastal vulnerability. And, there are many things I’m leaving out. It’s like winning an Oscar and having to thank everyone I work with on these projects!

Q: Who is your inspiration?

A (Erica): I am a big fan of many past and current cartographers who focus their craft on shaded relief. Shaded relief is a method for representing the peaks and valleys on maps in a natural, aesthetic, and intuitive manner. I also admire people who create infographics with their maps and people who map new and interesting topics.

Q: First mapping memory?

A (Jamie): In grad school, I was contracted by a land owner to map a forest being used for recreation and sustainable forestry in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina. I actually got paid to hike the trails and collect coordinates of all the infrastructure and points of interest! The deliverable was a poster size map, which (looking back) ended up being one of the ugliest maps I’ve ever seen.

Q: What books would you recommend for the map enthusiast?

A (Erica): Maphead by Ken Jennings (non-fiction)

A (Jamie): The Mapmakers by John Noble Wilford (non-fiction/history).

Q: How many states/countries have you stepped foot in?

A (Erica): I’ve been to 23 states and 6 countries (Canada, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Peru, and U.S.)

A (Jamie): All states except LA, MS, Al, AK, and HI. I’ve stepped foot in Chile, Argentina, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Spain, Sweden, Scotland/UK, Canada, South Africa, and China/Tibet, and the U.S., so 12 countries.

Q: What is one place you’ve mapped that you really want to go to!?

A (Jamie): Out of grad school I got a job as a GIS analyst with the National Zoo’s Conservation Research Center in Virginia. They do a lot of work in southeast Asia, and one of my big projects was mapping deforestation in Asian elephant habitat and ranges. I was particularly fascinated by the Upper Brahmaputra River Valley but never had an opportunity to go. The way the river braids and changes from year to year in the Assam area is incredible to witness via satellite imagery, but the upland forests neighboring Bhutan and Myanmar and the highlands leading towards China are what really appeal tome. Maybe someday!

Q: What are you looking forward to as a GIS professional?

A (Jamie): One fundamental thing that a GIS professional can always look forward to is discovery. Although much of the world has been mapped and the entire world is being touched in some way by humans, our senses of place and our understanding of relationships among people and nature provide an infinite world of exploration. Sounds cheesy, but I genuinely feel this way about my work.

Q: What is the power of maps?

A (Erica): Maps and spatial analysis are amazing tools at understanding our world. Not only do they communicate, explain, and reveal information, but most of us remember more through visual learning! The Nature Conservancy uses maps and spatial analysis in just about every conservation project we work on. They are powerful in answering the most pressing environmental questions of the day, which lead to positive conservation impact for both people and nature.

Explore our Maps and Infographics

Restoring America’s Forests Annual Meeting

Written and photographed by Ryan Haugo, Washington Senior Forest Ecologist

At the end of September several of us had the pleasure of representing the Washington chapter at the Conservancy’s annual North America “Restoring America’s Forests” conference in northern Arizona. Restoring America’s Forests is a formal network of over 13 demonstration landscapes across North America where the Conservancy is pursuing conservation through collaborative, ecological restoration on our national forests. Within Washington, the Restoring America’s Forests network incorporates both the Tapash Sustainable Forest Collaborative and the North Central Washington Forest Health Collaborative.

Northern Arizona is home to one North America’s largest, most ambitious ecological restoration efforts – the Four Forests Initiative (better known as 4FRI). Here the Conservancy has been instrumental in driving a science based approach to the restoration of millions of acres of dry, fire-adapted forests that are suffering from over a century of wildfire suppression.

The similarities (and differences) between the forests of Northern Arizona and eastern Washington are striking. Just as in eastern Washington, the dry forests of northern Arizona have experienced record breaking wildfires in recent years. The dry forests of northern Arizona are adapted to (and depend upon) frequent, low severity fire. Many of the recent “mega-fires” however, are well outside the range of conditions to which the forests are adapted. These fires threaten not only local communities but also the abundant fish and wildlife habitat, clean air and water, and recreational opportunities that draw people from across the globe to northern Arizona. Similar to eastern Washington, restoring the health and resilience of these forests depends upon using a combination of tools including mechanical thinning (logging), controlled burning, and managed wildfire to thin out the incredible density of small trees that have grown up in the absence of natural wildfire.

Finally, the economic viability of restoring dry forests in both northern Arizona and eastern Washington depends upon a forest products industry that has largely vanished from the local landscapes in recent decades. The differences are important to understand. The dry forests of northern Arizona are simpler, primarily with one tree species (ponderosa pine), and are typically much flatter. Both of these factors ease the implementation of ecological restoration treatments in comparison to eastern Washington.

A highlight of our 4FRI field tour including seeing first-hand the ingenious in-cab tablet technology that TNC has helped to develop. The tablets are designed to increase the efficiency of implementing ecological prescriptions during forest thinning projects. We also had the opportunity to visit the newly developed NewPac Fibre sawmill in Williams, AZ. This sawmill processes the trees harvested during restoration thinning and provides sustainable employment opportunities for local communities.

Most importantly however, was the opportunity to share successes, failures, and lessons learned amongst all of the Restoring America’s Forests landscapes. During these meetings we dive in deep to the policy, science, and partnership issues facing our work to restoring our National Forests. The Restoring America’s Forests network provides the opportunity to make and maintain personal connections between a forest ecologist in Washington State, a forest policy expert in Washington DC, a fire manager in Arkansas, and a forest manager in Arizona. These are powerful relationships and help to make the Conservancy such an effective conservation organization.

Learn more about our forestry work

Honoring Our Floodplain Champions

Natural resource leaders honored at first Floodplains by Design celebration

Written by Bob Carey, Strategic Partnership Director

Agencies and tribes recognized for their leadership in improving river management to improve flood protection, restore salmon habitats, improve water quality, and enhance outdoor recreation. More than 150 people came together to celebrate the Floodplains by Design Partnership and honor seven floodplain champions and project partnerships at a dinner Monday, September 12, in Seattle.

The Floodplains by Design Partnership, led by the Washington Department of Ecology, The Nature Conservancy, and the Puget Sound Partnership, identify and support large-scale projects that are built from the ground up by local governments, tribes and community stakeholders. Collectively the partnership is pursuing a vision of collaborative, integrated management delivering results to help Washington’s communities and ecosystems thrive.

In four short years, with the support of $80M in new state funding, the Floodplains by Design partnership has reduced flood risks to hundreds of families in 25 communities while restoring habitat along 10 miles of salmon-producing rivers, protecting 500 acres of farmland and creating new river access and trails.

“Floodplains by Design is not just a grant program, it’s a movement!” Bob Carey from The Nature Conservancy told the celebrants. “It’s a movement to put our shoulders together to make our communities safer from flooding, to make our salmon runs stronger, and to ensure future generations have local food, clean water, and recreational opportunities.”

Three locally-driven river management partnerships were recognized as 2016 Floodplain Luminaries, for their steadfast pursuit of an integrated, resilient river management program and delivering results in support of a prosperous community and healthy environment:

· The Yakima River Floodplain Project

· The Dungeness River Floodplain Partnership

· Puyallup Floodplains for the Future Partnership

Four organizations were honored as 2016 Floodplain Champions for their steadfast support of integrated, resilient river management programs that deliver results for a prosperous community and healthy environment, include:

· Washington State Department of Ecology

· US Environmental Protection Agency

· Tulalip Tribes

· Puget Sound Conservation Districts

Award presenters included Washington Sen. Karen Keiser, D-Kent, Rep. Richard DeBolt, R-Chehalis, Rep. Steve Tharinger, D-Dungeness, King County Executive Dow Constantine, NOAA Fisheries Regional Administrator Will Stelle, Puget Sound Partnership Executive Director Sheida Sahandy, and Washington Department of Ecology Program Manager Gordon White.

Presenting sponsors for the Floodplains by Design conference were Anchor QEA, ESA, HDR Inc. and Northwest Hydraulic Consultants. Dinner sponsors were Watershed Science & Engineering, Northwest Regional Floodplain Management Association and WEST Consultants. Funding for the Conservancy’s engagement in Floodplains by Design has been provided in part by the Boeing Company and The Russell Family Foundation.

Learn more about Floodplains by Design

A Cultural Exchange for Global Conservation

Photo credit: Bethany Goodrich, Sustainable Southeast Partnership

Photo credit: Michael Reid, TNC Canada

Every four years, the World Conservation Congress invites several thousand leaders and practitioners from government, academia, business, and indigenous and local communities to share their conservation goal, accomplishments, and challenges. This year, TNC Canada sponsored a group of Indigenous leaders from the Emerald Edge (British Columbia, Alaska, and Washington) to participate in this event and vocalize key issues felt on the ground in the Pacific Northwest.

The pre-congress gathering, which was held in O'ahu, Hawaii, brought together cultures from over 30 different countries to discuss global conservation problems and connect with each other to move towards creating cohesive protection for our planet and people. View the gallery above for photos of the World Conservation Congress gathering.

The Nature Conservancy's work in the Emerald Edge includes communication and collaboration with First Nations, tribes, and local communities throughout the region to protect and restore these valuable ecosystems for people and nature.

Learn more about our work in the Emerald Edge

The Many Gifts of Herring in the Emerald Edge

Nature signals spring. In Texas it is blue bonnets, in New England, robins, and for the Emerald Edge of Alaska, British Columbia and Washington, it is the return of herring.

Written & Photographed by Phil Levin, Conservancy Lead Scientist

For millennia, Pacific herring have been harbingers of spring. Historically, they returned in great numbers to spawn on kelp, seagrass and gravel throughout the Pacific Northwest. Their arrival was quickly followed by horde of sea lions, humpback whales, seabirds, and eagles all gorging on this plentiful prey. And in their wake, killer whales arrived to eat the sea lions and whales. With the arrival of herring, the waters of the Emerald Edge erupt with life.

And for the indigenous people of the Emerald Edge, herring eggs bring the first pulse of fresh food of the season. For the Haida, Tlingit and many other peoples, herring eggs are perhaps second only to salmon as the most culturally revered food. The Haida gather herring roe on kelp, while Tlingit set hemlock branches in the water and collect the thick layers of herring eggs that coat the limbs. Those who gather the delicacy will eat it themselves, share with family and friends locally and in distant communities, or trade for other products. Every feast and celebration will be accompanied by mounds of bright herring eggs that connect people to each other, their past and to the ocean.

Herring also signal the opening of the fishing season for commercial fishers. Many fishers who latter will focus on the lucrative salmon fishery, start their year with herring. In Southeast Alaska, over the last decade these boats scooped up an average of about 13,000 tons, annually. The unspawned roe is coveted in Japan, and in recent decades this has become a lucrative market. Both the income generated by the herring and the opportunity to break in new crew at the beginning of the season are critically important for many fisherman.

Herring are thus central for nature, for culture and for the economy of coastal communities. However, historic overfishing, pollution, coastal development and climate variability have resulted in many declining stocks of herring. In some places, the number of fish is so low that fisheries have been closed for years. In recent times, then, herring has not only announced spring, but has also marked a time of conflict.

Last year, my colleagues from the Ocean Modeling Forum (OMF) and I brought together more than 125 First Nation and Tribal Elders, governmental officials, scientists and environmental NGOs and asked what were the critical science gaps for science management. As one of the directors of the OMF, my role is to connect diverse types of knowledge and bring it to bear on pressing ocean management issues. In the case of herring, we learned that the extensive traditional knowledge of indigenous people is often marginalized in management, and the cultural costs and benefits of herring are not adequately considered in decision making.

To fill these gaps the OMF created a working group of 18 social and natural scientists, traditional knowledge holders, commercial fishers, and resource managers to tackle this problem. I just returned from co-chairing the 3rd meeting of the OMF herring group (with Dr. Tessa Francis from the University of Washington Puget Sound Institute) which met in Sitka, Alaska. The group has made great strides in incorporating traditional knowledge into quantitative ecological models – the language of fisheries management. Working collaboratively across our professional silos, we have developed the means to formally examine management alternatives to determine their ecological, economic and cultural outcomes—the triple bottom line.

After the OMF meeting concluded, I had the privilege of visiting historic and current herring spawning grounds with Harvey Kitka – an elder of the Sitka tribe. Each cove and beach seemed to have a story of plenitude and demise. Harvey spoke about the time when herring were so abundant that they jumped from the water and the crack of their bodies hitting the ocean’s surface would echo across the Sound like hail. Those days are gone. Instead, Harvey pointed to islands were there was just a little spawning here and a little spot there. He spoke with sadness about the present, but was always optimistic about the future, and the work we are trying to do.

Solving difficult conservation problems, like herring conflicts along the Emerald Edge, will require new approaches and innovative thinking. My experiences working with a diverse group of people with vastly different perspectives on herring, suggest that given the chance people can rise to the occasion and tame these wicked problems.

Learn more about our work in the Emerald Edge

Collaboration Works for Forest Restoration

Written by Lloyd McGee, Eastern Washington Forests Program Manager

Stewardship project launched in the Colville National Forest.

Last week we celebrated with Congresswoman Cathy McMorris-Rodgers to kick off an innovative forest stewardship project in the Colville National Forest. This first of its kind stewardship partnership between a national forest and a private company is a pilot aimed at restoring the 54,000-acre Mill Creek watershed—a beloved area near Colville that’s been well-used by people for a century.

Vaagen Brothers Lumber (VBL) will carry out forest treatments on more than 17,500 acres of this landscape. By removing smaller trees and leaving the big ones, this project will reduce the threat of wildfire while at the same time supporting local jobs, as small-diameter timber is harvested and processed by Vaagen Brothers.

But it’s not just harvest—these are complete forest restoration projects that include forest thinning and controlled burning to reduce forest fuels, restore streams and riparian zones, repair roads and close some roads harmful to fisheries and water quality, and restore wildlife habitat. No old growth trees will be cut.

Congresswoman McMorris-Rodgers has been instrumental in laying the groundwork for this project, working with stakeholders and the Forest Service to develop this public-private approach that enables the private sector to fund the presale environmental requirements, carried out here by Cramer Fish Sciences.

This approach was developed by the Northeast Washington Forestry Coalition, or NEWFC, of which The Nature Conservancy is a member. NEWFC is an alliance of timber companies, conservationists, business owners, tribes and forest professionals.

Work on the A to Z began last week after an onsite ceremony Aug. 12 with Congresswoman McMorris-Rodgers, VBL President Duane Vaagen, VBL Vice-President Russ Vaagen, VBL Resource Manager Josh Anderson, Lloyd McGee from the Conservancy and NEWFC, NEWFC Executive Director Gloria Flora, Stevens County Commissioner Steve Parker, Colville National Forest Supervisor Rodney Smolden and other local community members. Sen. Maria Cantwell has also supported this project. She was unable to attend the Aug. 12 ceremony, but visited the area the day before and met with stakeholders.

Learn About Our Forestry Work

Phil Levin, Noted Conservation Scientist Joins Nature Conservancy, University of Washington

SEATTLE, WA — Conservation scientist Phillip Levin is stepping into a newly created joint position as the Lead Scientist for The Nature Conservancy in Washington and Professor of Practice in the University of Washington’s College of The Environment.

Levin says he is looking forward to tackling the big challenges and scientific questions facing us in the region by bringing together the practical work of a conservation organization working locally and globally, the knowledge and research capacity of a major university and the science, technology and innovation leaders in the region.

“I love the phrase ‘professor of practice,’ ” he said. “We’ll have the opportunity not only to answer very specific questions about how best to achieve conservation outcomes, but also discover new questions and bring them forward.”

“The Nature Conservancy has always used science as a foundation for our work,” said Mike Stevens, the Conservancy’s Washington State Director. “What Phil brings us in this new position is a clear ability and focus on how to deploy science and people to solve really the big challenges that are facing us today.”

“UW and the Conservancy have a history of working together,” said Dr. Lisa Graumlich, Dean of the UW’s College of the Environment and Mary Laird Wood Professor. “This new position takes our collaboration to a higher level by fully uniting our considerable research expertise with the Conservancy’s leadership in conservation on-the-ground. If we want to make sure our research has a positive impact on environmental challenges, it needs to reach the right people. Phil is the best person to lead the way: He has a long, successful career based on building teams of people from many disciplines who create better resource management plans by working together. We’re extremely excited for our students to learn from his years of experience.”

Levin will work in the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences and Center for Creative Conservation within the College of The Environment.

Read a Q&A with Levin here

Levin comes to UW and the Conservancy from the NOAA Fisheries Science Center in Seattle where he was Senior Scientist and Director of the Conservation Biology Division.

Levin has received the Department of Commerce Silver Award and NOAA’s Bronze Medal for his work on marine ecosystems, and the Seattle Aquarium’s Conservation Research Award for his work in Puget Sound

He has published over 150 scientific papers in peer-reviewed journals, book chapters and technical reports, and his work has been featured in such news outlets as NPR, PBS, the BBC, MSBNC, The Economist, among others. His research into Puget Sound’s sixgill sharks was recently featured on “Wildlife Detectives: Mystery Sharks of Seattle” on KCTS-9.

Levin is an editor of the scientific journal, Conservation Letters, recently served as President of the Western Society of Naturalists, and has served on numerous editorial boards and scientific advisory panels.

He received his Ph.D. in zoology from the University of New Hampshire in 1993 and was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of North Carolina.

Thinning for Resiliency

Written & Photographed by Zoe van Duivenbode, Marketing Intern

I recently drove to one of our central cascade properties to meet with field forester, Brian Mize, to learn more about how we plan to manage and restore our forests. Prior to my visit, I was unfamiliar with logging as a tool for restoration and was eager to find out how removing certain stands of trees can actually benefit the forest by improving health, increasing fire resiliency and creating habitat for wildlife.

Over the last decade, fire suppression has been a high priority among land managers and owners in hopes to protect property and habitat. However, this push away from fire has slowly changed the landscape of our native forests, allowing for certain species to thrive where they typically would not and creating denser tree stands. This shift creates a problem for land managers and nearby communities because it increases the risk and severity of forest fires. Certain trees, like grand fir, are more vulnerable to forest fires and have become more common among tree stands in central cascade forests. Also, forests with high density stands forces trees to compete with each other for resources, increases the amount fuels for fires and reduces habitat suitability for wildlife.

The Nature Conservancy plans to apply restoration thinning techniques on select units of our central cascade properties to create a more historic and variable forest structure which will benefit communities, wildlife and nature. On July 9th, TNC is inviting the public to one of our central cascade properties to see our restoration first hand and learn more about the benefits of restoration thinning. Our field forester will share more about the science behind thinning, and will answer any questions about our restoration work.

Join us for Forestry Day and see our work!

Learn more about our Central Cascade Preserves

Time for Your Thoughts

Guest blog and photos from Susan Zemek, Washington Recreation and Conservation Office

State officials and legislators are looking for your thoughts about if and how to revise the 25-year-old Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program (WWRP), which is the state’s grant program for wildlife conservation lands, state and local parks, trails, natural areas, and working farms and ranches.

Please take a short survey by Oct. 18 to share your insights about the WWRP.

The Legislature created the WWRP in 1990 to give the state a way to invest in valuable outdoor recreation areas and wildlife habitat conservation lands. They wanted to protect critical habitat and make sure our kids, grandkids, and future generations had places to recreate, and they wanted to do it before the land was developed. In its 25-year history, the grant program has funded projects in nearly every county of the state.

As state officials review the program, they are looking to see if the program is accomplishing what it set out to and what might need to change going forward. So now’s the time to give them thoughts.

Seattle PrideFest 2015

Tell us why you love nature!

Video by Cailin Mackenzie, GLOBE intern

Our short video celebrating diversity and conservation! A compilation of clips from our booth at Seattle’s 2015 PrideFest.

Parenthood, Conservation and City Living

Finding ways to engage city kids in conservation

Written and Photographed by Jamie Robertson, Spatial Analyst

“Outside, Daddy!” demands my toddler, Rowan. She wants to be out of the house exploring the community garden, following the hoot of an owl, or surveying the bay below our Tacoma neighborhood. I hear it multiple times a day and will never tire of it. She loves being outside – out adventuring – and I wish more than anything that she always will.

Being a conservation geographer, my career and my personal life meet at a crossroads of place and a respect for the natural things supporting us in this world. As a parent whose childhood was spent freely wandering many undeveloped acres of wooded hills, playing in healthy clear creeks, and dancing around May Poles in what wasn’t quite a hippy commune but let’s call it one anyway, I recognize “place” played as large a role in shaping my sense of discovery, wanderlust, and career as the people I shared those experiences with. And Rowan’s childhood place is certainly different from my own.

My wife Courtney and I recently moved back to Washington after each discovering its lures before we even knew each other. We are from North Carolina, though we met, fell in love, and had Rowan in Colorado. Our landing in Tacoma was a surprise, but our decision to raise Rowan in this state was absolutely deliberate. As it turns out, Tacoma is arguably the prettiest city in the Pacific Northwest. Mt. Rainier looms, old growth trees tower in vast Pt. Defiance Park, the waters of Tacoma Narrows and Commencement Bay surround half the city, downtown museums and theaters provide an impressive cultural and aesthetic appeal, and beautiful Craftsman, Victorian, and Tudor homes with lush gardens spread across the steep hillsides. Despite its rough history and typical urban issues, Tacoma is a wonderful place to raise our family.

But with city living – or maybe I should say modern living – comes a struggle. How do we allow Rowan enough freedoms to discover her own paths? What is truly necessary for her to grow respect for the natural world?

Granted, my daughter is still a toddler, but finding ways to engage city kids in conservation is a necessary strategy for all people concerned with natural or urban wellbeing. I believe tomorrow’s conservationists will increasingly be born from an urban experience which differs so vastly from the back-to-nature background of so many conservationists today. Indeed, this will be necessary as urbanism will only continue to influence and control the fates of the natural world that shaped me so profoundly and which will keep our social and economic systems running well into the future. Freedom to discover outside leads to respect for nature and is fundamental to engaging all children, I believe.

In my job, discovery means mapping out the world around us to help Washington understand the natural world and the factors impacting it so we can determine collectively how to address conservation issues. As a parent, discovery means finding ways to teach Rowan skills of self-reliance and to build a foundation of confidence she will need to adventure on her own. …But for now, I’ll be sure to keep a watchful eye when she sprints out the door.

Learn more about how you can share the love of the outdoors with your kids.