A neglected parking lot has transformed into vibrant urban agricultural land and a leading example of how green stormwater infrastructure can be implemented at the community level.

Restoring Ballinger Open Space

For years, a neglected 2.6-acre green space in Shoreline has sat adjacent to Ballinger Homes, a low-income subsidized housing community. This neglect has led Ballinger Open Space to be filled with invasive weeds that include knotweed, Himalyan blackberry and English ivy. A multi-pronged partnership aims to restore the health of this riparian area by turning back the clock, clearing invasive weeds and planting trees. This will increase access for young people to nature, cut air pollution and treat stormwater.

Trees are rooting community in Rainier Beach

Hillside Paradise Parking Plots growing more than food

October was for tree planting all around Puget Sound

Boeing Funds Trees for the Health of Puget Sound

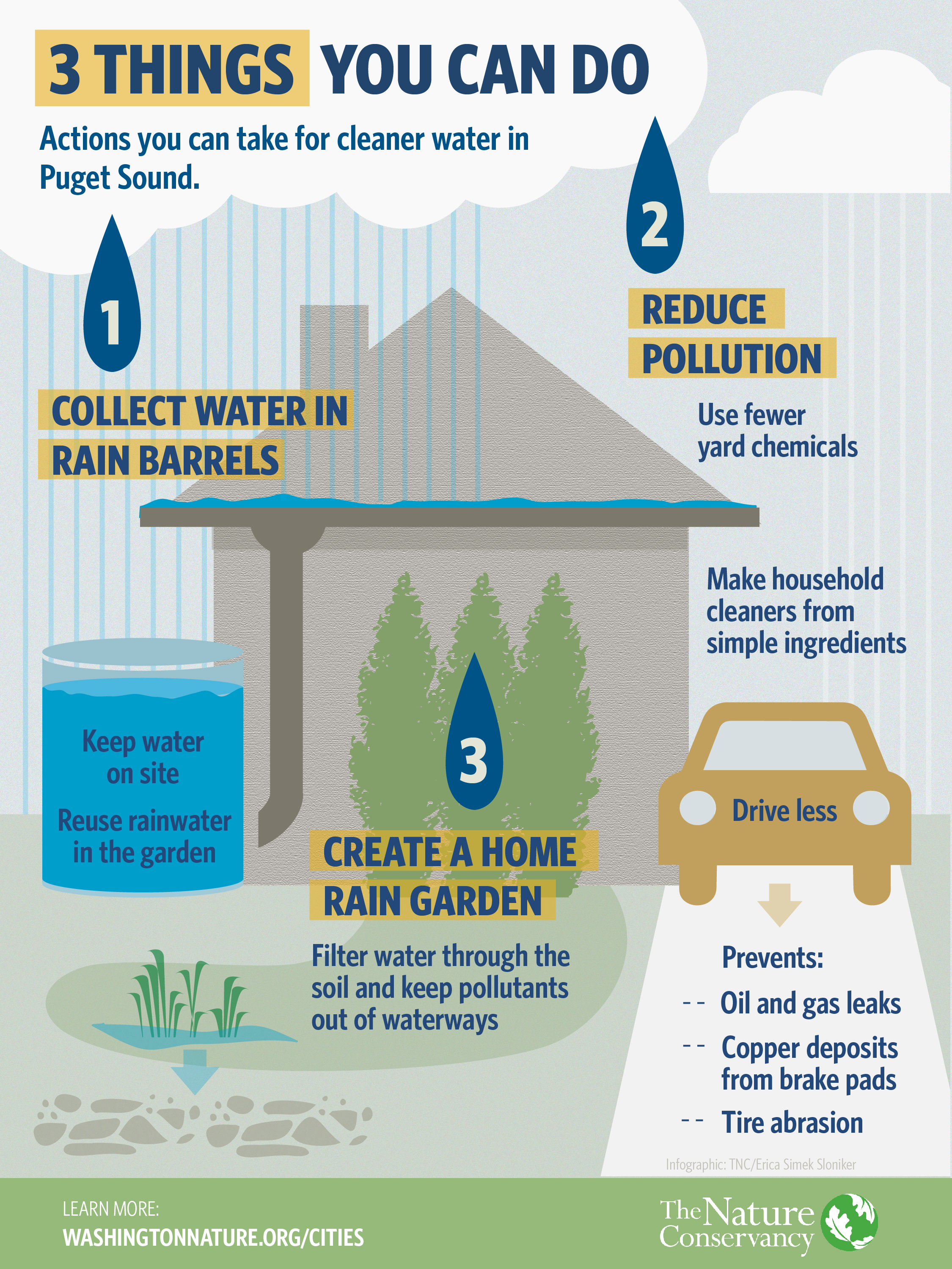

Take Action for a Cleaner Puget Sound

With all this talk about the negative affects polluted run off has on Puget Sound, here are a few things you can do to make a positive difference. Actions like capturing rain, building rain gardens and driving less can all help reduce the impacts of polluted run off and move towards creating a cleaner and healthier Puget Sound. Explore the infographic below to learn more about what you can do.

Infographic Created by Erica Simek Sloniker

Rolling Back the Pavement

Written by Tammy Kennon

Photographed by Melissa Buckingham, Pierce Conservation District

Pavement does not have to be permanent. The Puget Sound Conservation Districts, a collaboration of the Puget Sound’s 12 districts, reminds us that it’s possible to bring nature back into our urban landscapes.

Tacoma’s Hilltop neighborhood has reclaimed a derelict, crumbling parking lot and gained a multi-use green habitat. The project, completed in June, now serves dual use as a community gathering space and a natural filtration system for otherwise polluted runoff. The transformed space now filters on-site more than 130,000 gallons of polluted runoff a year.

Thanks to its natural beauty, economic growth and the thriving tech industry, the Puget Sound region is one of the most rapidly urbanizing areas in the nation. Our population grows by more than 200 people every day and by some estimates will top 7.5 million by 2030. Often, this growth puts our green spaces in a losing tug-of-war with urban development. Sprawling pavement, rooftops and roadways send increasing levels of polluted runoff into our vital waterways, creating one of our most urgent environmental challenges.

Reclaiming even small patches of pavement and restoring nature’s filtering systems can have a significant effect in mitigating stormwater pollution, while at the same time reenergizing urban neighborhoods and improving quality of life within our communities.

For the Tacoma Hilltop project, the Pierce Conservation District (PCD) enlisted more than 100 members from the community to help select a site and participate in its transformation.

“We partnered with Tacoma’s Healthy Homes Healthy Neighborhoods program to identify unfunctional space,” said Melissa Buckingham, Water Quality Improvement Director of the Pierce Conservation District. “Feast Art Center was moving into the area and wanted to create an outdoor community space. It just all came together.”

With funds from Boeing and The Nature Conservancy, the Feast Arts Center, an art school and gallery, converted 4,500 square feet of derelict pavement at south 11th and south Sheridan into a vibrant community gathering space featuring an outdoor silent movie theater, rain garden and a green multi-use lawn for events. The perimeter includes a drivable area to accommodate a variety of community events that might utilize food trucks or blood drive vehicles.

“The building and the lot had been a vacant eyesore for many years, so many in the community are grateful for the change,” said Todd Jannausch, co-owner of Feast Arts Center. “We use the space to host a variety of free events, classes and performances for the community.”

Bringing nature back into our urban environment can do more than just energize the neighborhood. A growing body of research suggests that living near green space inspires physical activity, improves neighborhood safety, boosts the economy and helps children learn. The bottom line: It’s easier being green!

The success of the Feast Arts Center depave project is a welcome reminder that we can reclaim a natural habitat in the urban environment, proving that humans and nature can thrive together in the same space.

The Truth About Puget Sound

Written by Stephanie Williams, Program Coordinator

The Pacific Northwest is known for its good looking bodies… of water, that is.

If people don’t know much about Puget Sound, they tend to at least know that this region has a wealth of gorgeous views of blue lakes, tree-lined rivers, waterfalls, and meandering creeks, not to mention the Sound itself. While this is something to boast about, it is also quite deceptive. These breath-taking views are hiding a serious problem that can only be seen with an up-close look. The water in Puget Sound looks healthy and is often described as pristine, but the truth is that it is in very bad shape.

What isn’t easily visible in the picturesque Elliot Bay, Skagit River, or Lake Washington is polluted run-off from our urban and suburban areas. While it may not be a floating plastic bag or a six-pack ring, the poster children of aquatic litter, polluted run-off is having a severe impact on salmon, marine mammals, and the entire ecosystem (humans included). It is the number one threat to water quality in Puget Sound.

But what is polluted run-off? What is this ghostly and invisible thing?

Polluted run-off, which is also referred to as “stormwater,” is rain water that rushes over pervious surfaces, such as buildings, roads, and sidewalks collecting dangerous oil, bacteria, chemicals and other pollutants along the way. Unlike sewage, which passes through treatment facilities, polluted run-off ends up in the nearest body of water dirty and untreated.

Imagine what your city or town looked like before humans built there. It was most likely a rich forest, lush with vegetation and healthy soils. Back then, the rain would catch on trees and be absorbed into the forest soils, which both slowed and cleaned the water as it made its way toward Puget Sound. Over time people greatly changed the landscape by erecting tall buildings, houses, and roads, all with hard surfaces that left nowhere for the rain water to go. To avoid flooding, storm drains were built to pipe the rain water away from the city to streams, lakes and the Sound. Water that used to soak into soils and groundwater, supporting a healthy ecosystem, now runs off and causes more frequent erosion and flooding in addition to its devastating impact on salmon and other species.

The problem of polluted run-off is not as simple as sea turtle caught in a six-pack ring. It is very complex and its inconspicuous nature only makes it more difficult to bring to people’s attention. Check out cityhabitats.org and washingtonnature.org/cities to see what The Nature Conservancy and its partners are doing to raise awareness of polluted run-off and affect change for salmon and for ourselves.

How Can I Make My Home More Green

Interested in building a rain garden but don't know how? Follow these guidelines and help us create a clean and healthy Puget Sound!

Creating, Connecting & Learning with Habitat Network

Did you know that the plants and natural features along your street, in your yard, and at your favorite playground or park improve your quality of life AND provide habitat for dozens of plants and animals?

The Nature Conservancy and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology have launched Habitat Network, a free online citizen science tool that invites people to map their outdoor space, share it with others, and learn more about supporting wildlife habitat and other natural functions in cities and town.

In Puget Sound, 75% of cities and towns are covered in impervious surfaces. These hard surfaces, like driveways, roads, and roofs, prevent rainwater from soaking into the ground. When it rains, water running off impervious surfaces picks up pollutants and debris. The polluted runoff can then end up in our nearest water body.

Habitat Network offers alternate solutions for yards, parks and other urban green spaces to reduce polluted runoff while supporting birds, pollinators, and other wildlife. Habitat Network can be used on properties of all sizes and types – from a shared urban garden in a city park to a large suburban backyard or a school yard.

What can a Habitat Network help you do?

- Manage rainwater

Attract a variety of birds to your home, school, or business

Help protect bees and other pollinators

Compare your map to other network members and get inspired!

“Science shows us that small changes in the way properties are managed can make a huge impact towards improving our environment,” said Megan Whatton, project manager for Habitat Network at The Nature Conservancy. “Creating and conserving nature within cities, towns and neighborhoods are key to global conservation.”

The mapping tool is also a social network, inviting participants to share information and learn from their neighbors. And over time, the self-reported information from citizen scientists using the Habitat Network will provide data the Conservancy can use to understand how much habitat exists in our cities and towns and what role that habitat can play in benefiting wildlife and humans.

In Washington, we’ll be using it to track progress on our City Habitats’ goal of building 20,000 rain gardens in the Puget Sound region.

Help us learn more about habitat in our cities and towns by making map on Habitat Network! Go to www.habitat.network to sign up for an account and get started mapping, sharing, and learning about sustainable practices you can implement in backyards, schoolyards, parks, and corporate campuses.

Visit habitat.network to join!

Rain Gardens: Below the Surface

Rain gardens are a great way to make any neighborhood shine. But there is more to a rain garden then the colorful flowers, trees, and grasses you see at the surface. See the image below to learn more about what is happening underneath a rain garden.

Infographic created by Erica Simek Sloniker

Learn more about rain gardens here

Sign up for Make a Difference Day

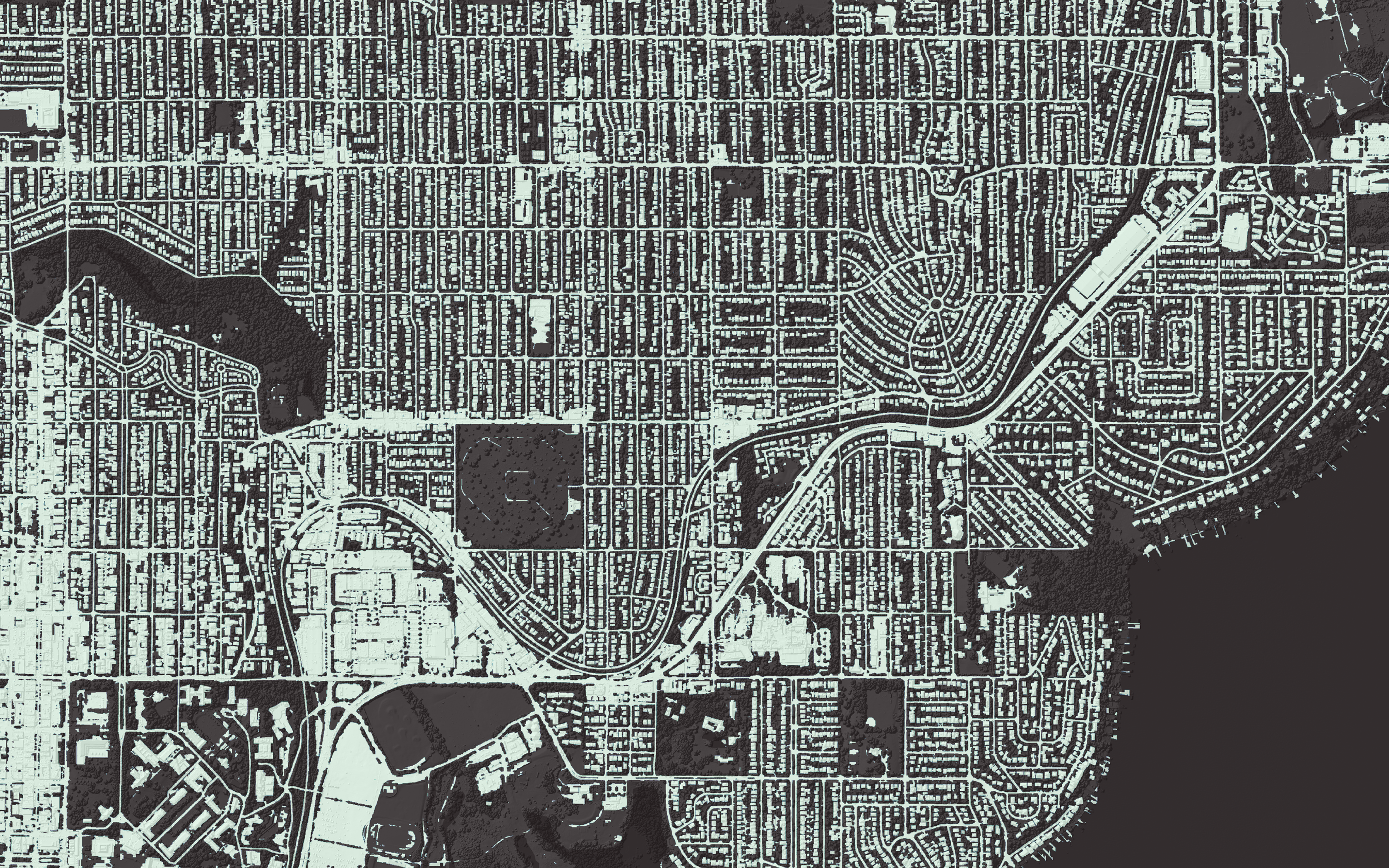

Puget Sound: Our home at Risk

As more people are moving to cities, our surrounding environments are undoubtedly changing. Washington cities are some of the most rapidly urbanizing places in the nation. So what does that mean for Puget Sound? Explore the infographic below to learn more.

City Habitats: Why Puget Sound Needs Our Help

More and more of us are living in cities! As our planet, state and region become more urban, wildlife, water and other natural resources are at risk. One of the biggest threats to Puget Sound is stormwater runoff. Stormwater runoff is the biggest source of pollution to Puget Sound, affecting aquatic life and public health. Here’s why our iconic rainfall is an issue, and what we can do to help protect Puget Sound.

Infographic created by Erica Simek Sloniker

Learn about our work in Cities

Solving Stormwater: Watch the video

An Urban, Suburban Trek in Bellevue

Written and Photographed by Carrie Krueger, Director of Marketing, The Nature Conservancy in Washington

We want to know: Where do you see Nature Nearby? Share your stories and images below for the chance to be featured on a future blog post!

Our state- and our world – are becoming increasingly urban. For some of us, that means that what was once a rural suburb is now a bustling city filled with homes and high rises. Yet as we grow, it’s vital we keep a strong connection to nature including wildlife corridors, water retention areas and places we can go for peace and solace.

Bellevue has gone from sleepy bedroom community to hub of commerce and industry. But its string of pearls is a connected series of parks allowing us to travel from Lake Sammamish to Lake Washington through forests, wetlands, farms and gardens.

Most recently, I began this trek at Weowna Park on the shores of Lake Sammamish. In the crisp morning air, we climbed through lush, mossy forests, across streams, occasionally pausing to look back at the lake below. We emerged into a residential area and wandered through lovely neighborhoods, past the Lake Hills Park.

Phantom Lake and the surrounding wetlands were teeming with birds, and as we made our way through the Lake Hills greenbelt, many walkers carried binoculars. The meandering greenbelt features towering trees, wetlands and even agriculture in the form of blueberry farms where signs of a tasty harvest next summer are just beginning. At the northern end of the greenbelt is beautiful Larson Lake – so peaceful though thoroughfare traffic, shopping and other signs of urban life are close by.

Following the trail behind and around Sammamish High School, we were again reminded that we are in the middle of a burgeoning city where the already large high school is being expanded to accommodate growth. But just beyond, we were plunged back into nature, joining the powerline trail and then the forest behind Kelsey Creek Farm. In the creek, salmon still spawn and the surrounding wetlands hold and filter water. In the middle, farm animals are a draw for kids – and their parents.

Just three blocks of neighborhood walking took us to the rich forest east of Wilberton Park. Ballfields and a playground on the other side connected us to the Bellevue Botanical Gardens. Here there is much to see in the form of immaculate, groomed gardens but also a wild canyon experience complete with a suspension bridge.

From the serenity of the gardens, we experienced the most urban and perhaps least enjoyable part of the trek – a brief walk directly parallel to the much-used 405 freeway. It’s hard to ignore growth and demands on nature when walking next to a jam-packed freeway. Fortunately we were quickly under the 405 and into the spectacular Mercer Slough. It’s remarkable that such an important and natural place exists in the shadow of downtown high-rises. Heron, turtles and other wildlife are common sights and this time of year, hints of spring popping up everywhere.

From the slough, we shared the trail with bicyclists as we made our way to the shore of Lake Washington at Enatai park. The park is a perfect place for considering the interface between nature and development because it is set literally underneath the I-90 freeway. Yet looking out on to the lake, nature abounds as does wildlife and recreation.

Our trek through Bellevue demonstrates many of the benefits of creating a strong tie to nature in the midst of intense growth. Parks, greenbelts and even small pockets of plants foster wildlife, cool the air in the summer, clean urban storm water runoff and give us a place to retreat and reenergize.

Puget Sound: Outside Our Doors Inside the Radio

Audio provided by KOMO News Radio

Our Director of the Puget Sound Program, Jessie Israel chatted with KOMO News Radio about Puget Sound Day on the Hill and the brand new Nature in Cities report. Listen in above!